By Ebele Orakpo

On this hot and sunny afternoon, on a slightly busy Lagos road, a middle-aged woman, dressed in the traditional iro and buba, was trying to cross the road, holding a walking stick, obviously vision-impaired.

“Hmmm, na only God know wetin she don put her hand into, the evil she had done! This is not ordinary!” snorted Bisi, turning to her friends – Aina, Jimi and Tade as they watched the lady trying to cross the road.

“For all I know, she may be a witch,” said Jimi.

“Habaa! exclaimed Tade who had a look of pity on his face as he watched the woman.

“Now, now, now, she don become witch or evil woman simply for being unable to see? How is that her fault? It could have been any of us,” he said. Before he could complete the sentence, a chorus of “God forbid, it’s not my portion,” rang out simultaneously from the three others.

“Tell me, if she is not evil, how come no member of her family is helping her get around?” interjected Bisi. Continuing she said: “Life is mysterious, whatever a man sows, he reaps. If you sow good, you reap good and if you sow evil, you reap evil.”

As if God heard the silent prayer of the blind lady and saw her struggles and pain, as the vehicles were not ready to stop for a second to let her cross, a young man seemingly came out of nowhere, went to her, held her hand and helped her cross over to where she was headed. This is the typical experience of an average person living with disability in Nigeria. In this report, Saturday Vanguard speaks with stakeholders on the struggles of persons living with disabilities, what the law says and way forward.

Excerpts:

Uchechukwu Muojekwu, a practising registered nurse, licensed in 2022, shares her personal experience with Saturday Vanguard from her base in Anambra State.

The journey

Uche Muojekwu was not born with visual impairment. All was well with her eyes until October 2024, when life played a fast one on her. She was diagnosed with optic nerve atrophy, a medical condition that causes the degeneration of the optic nerve which greatly impacts and impairs vision. According to Uche, ”this affected my life greatly in the most negative way possible.” Not one to succumb to the vicissitudes of life, Uche, instead of tucking her tail, decided to face her predicament head-on.

Passion

Said Uche: ”I have always been very passionate about mental health and anything that has to do with Psychiatry. So after my diagnosis in 2024, I just knew it was time to delve into a career path that I have been very passionate about, especially now that I need mental health care myself. I decided to take it up as a specialty in nursing so I looked out for schools that offer the course. I mentioned it to a close friend and she said she would let me know when their school form is on sale which she did.

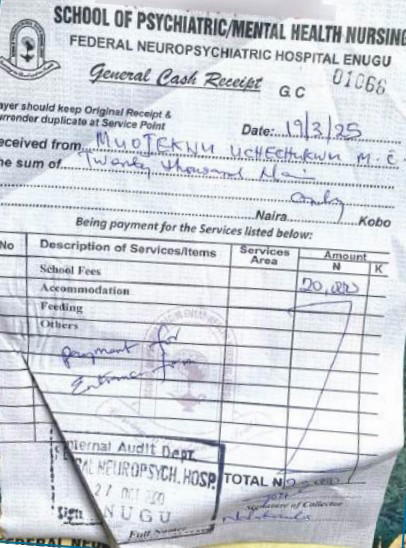

“I stay in Anambra so I sent her money to purchase the form for me. I still have the receipt of the form. It was from her that I learnt about who the Students Union Government, SUG president at that time was because we all attended the same school, but we were a class or two ahead of him. I reached out to the school through the SUG president and explained that I am visually impaired and will be needing help.”

Three options

“I gave them three options to at least provide one for me: One, make my exam questions in bold font so that I won’t have to strain my eyes. Two, assign an examiner to me to read out the questions. Three, allocate extra time to me. That was before the exam and I still reminded them a few days to the exam date.”

D-Day

The D-Day, March 22, 2025 finally arrived! Uche got to the exam centre as early as 7:00 a.m and met with the SUG president who took her to two female examiners and told them that she is the lady he spoke to them about. Thereafter, they asked her to come out of the sun and sit in a shade because they were all in an open space.

“After the vetting of our documents which ended around 10:am, the exam eventually commenced at 5:00pm.” She was totally unprepared for what followed: ”My question papers were not different from every other person’s. I tried to see if I could strain my eyes to read but I couldn’t. I called the attention of an examiner, a lady in her 30s or 40s, Mrs. Onukwuli, and explained to her that I am visually impaired and asked if they could allocate extra time to me or call an examiner to read out the questions to me.

“She said: ‘If you knew you were not able to read, why did you come to school?” Talk about rubbing salt in a wound! As if that did not inflict enough pain,”she said it a second time and walked away’.”

Death knell

Uche broke down and wept but not ready to throw in the towel, she quickly wiped her tears and called the attention of another examiner. “She was kind enough to take me to meet the Provost, Mr. Vitus Nwagu who happened to be inside the exam hall. We walked up to him and I narrated my story to him and mentioned that I had informed them before now through the SUG president and asked if they could assign an examiner to me or give me extra time; I also mentioned that I had my medical reports and could present them to him if he wanted. “That won’t be necessary; there is NOTHING we can do for you,” Nwagu said with a note of finality. “I asked why? Does that mean I should leave and stop writing the exam?.

“I was in tears. He said I should answer the ones I could see and leave the ones I couldn’t see. I told him there was no way I could continue with the examination since they were not willing to help me in any way. He said before I leave, I should sign out. I said I wasn’t going to sign out because I wasn’t leaving willingly. I dropped my question papers and cried my way out of the hall.

“When I got outside, I called my mum, and she calmed me down. I stopped crying and headed home. Before I got home, my dad was already calling me. He was very heartbroken,” Uche said.

CP child thrown out

Weighing in on the matter, Prof. (Mrs) Joanne Umolu, founder and former Director of Jos-based Open Doors for Special Learners and a former lecturer in the Dept. of Special Education, University of Jos, regretted that Nigeria still has a long way to go.

She said: “A parent came to me crying. She had a child with Cerebral Palsy, CP who she enrolled in nursery school. The school told her to withdraw her child from school because other parents refused to put their children in the same school with the CP child. They thought CP was contagious. So he’s been in Open Doors since then. He is a wonderful boy who walks by pushing a wheelchair.”

Loss of dignity

Reacting to Uche’s story, the Executive Director, Centre For Disability and Inclusion Africa, Mr. Yinka Olaito said losing one’s sight in Nigeria “comes with something far worse than blindness: the loss of dignity. From exam halls, to hospital corridors and government offices, visually impaired citizens are routinely denied basic accommodations, shamed for asking for help, and quietly pushed out of opportunities others take for granted.

“This is not a story of personal misfortune; it is an indictment of a system that treats disability as an inconvenience, not a question of rights. That indictment simply found a human face in Uche. Uche is not asking for sympathy. Her ambition collided head-on with an institution that appears unwilling or unable to understand that inclusion is not charity but a legal and moral obligation. What followed, by her account, was a master class in bureaucratic cruelty.”

Inclusion, not segregation

Speaking on her experience as an Early Year/Montessori/Special Needs Director, Mrs. Precious Okaka pointed out that there are different special needs on the spectrum – physical, medical, behavioral etc. and they are all treated differently.

“As teachers, we talk to the parents and children to make them understand that these children are special, they are peculiar and with time, some of them develop love and friendship towards these children. Some parents say they don’t want their children to be infected even when they know the conditions are not infectious.”

Continuing, Okaka said: “I remember when I had a child that always had seizures. At some point, the children got to understand when the child is having a seizure, and they would rally round, asking me what they could do to help and make the child comfortable. So if you have a special needs child in your class, you need to talk to the other children to understand that the child is not like them, that God created him special and that is why he is behaving the way he is behaving; it is not something he can control. As little as four years old, they understand and get to know that ‘oh, this child can’t sit in one place because he has hyper-attention disorder syndrome; this child can’t write because he is highly autistic; this child can throw tantrums and shout because something is going on in the brain.”

What the law says

Olaito said that the law is crystal clear on this. “The 1999 Constitution guarantees equal and adequate educational opportunities and prohibits discrimination.

The Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018 goes further, mandating inclusive education and reasonable accommodation in all learning and assessment processes. For visually impaired candidates, this includes Braille or large-print papers, audio or electronic formats, approved scribes, extended exam time, quiet venues and the use of assistive devices.

“Denying these accommodations is not a harmless administrative lapse. It is illegal. In effect, it criminalises disability by turning a physical condition into grounds for exclusion.

“It seems that while policy statements and appointments multiply, lived experiences suggest that implementation remains dangerously thin,” he said.

Susan Ihouma Kelechi, a disability advocate puts it this way: “Keeping quiet without punishment is inappropriate. Today, it is Uche; tomorrow it can be another person.”

On his part, the National President of Joint National Association of Persons with Disabilities, JONAPWD, Abdullahi Usman, described Uche’s case as “a display of ignorance in a federal institution” and pledged to push for accountability.

Meanwhile, Part V, Section 18, of the Discrimination Against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act 2018 rejects every form of stigmatisation against persons with disabilities.

It advocates Mandatory Inclusivity, Trained Personnel and Curriculum Integration.

Way forward

On the way forward, Olaito said educational institutions ”must stop improvising and start institutionalising disability support services. Professional bodies must adopt and enforce clear, standardised accommodation protocols. Regulators and supervising ministries must move beyond issuing hollow circulars. And the National Commission for Persons with Disabilities must show that it has teeth—not just a letterhead.

“The media, too, has a responsibility. Disability must be reported as a rights issue, not a charity case.

When a candidate asks for Braille, assistive technology or extra time, they are not seeking an unfair advantage; they are demanding a level-playing field,” he said, adding: ”Until Nigeria understands that inclusive assessment is not optional but foundational to education, our claims of progress will remain hollow. Disability is not inability. Exclusion is.”

Awareness creation

“For parents, schools are creating awareness. During my program in the University of Lagos, we as students had to organise talks to educate our community, schools and parents. These children are with us and we have to know how to manage and not segregate them,” Okaka said, noting that some parents don’t even understand that their children are on the spectrum until they get to school and begin to exhibit certain behaviours.

No response from school

Uche said since the incident happened, nobody from the school has reached out to her. At the time of writing this report, WhatsApp messages to the school, Federal Neuropsychiatric Post-Basic Mental Health Nursing School, Enugu, were not responded to.

Conclusion

Round pegs must be placed in round holes. Everyone, without exception, has one disability or the other, whether we know it or not. It is part of the human experience. No one has it all so be kind and empathetic always.

“It has been very difficult and tough and I can’t even begin to explain how that incident made me feel but over all, it has strengthened my resolve to still become a mental health practitioner because a lot of persons’ mental health depends on mine,” Uche said.

She advised stakeholders and those in positions of authority to ensure they put the right people in the right positions. My mother of blessed memory always asked professionals like doctors, nurses, teachers and pastors if they are called or they called themselves. There are certain qualities that are inbuilt in those who are genuinely called into these professions.

”We cannot keep having people who do not care, people who lack empathy in the mental health space,” Uche said, adding that she is still looking out for schools and sponsorships in the UK and US to pursue her dream.

The post Seeing is not Believing: Cruel reality of living with disability in Nigeria appeared first on Vanguard News.