Introduction to Water Scarcity in Nigeria

Nigeria faces a growing water crisis, with over 60 million people lacking access to clean water despite the country’s abundant freshwater resources. Rapid urbanization and population growth in cities like Lagos and Abuja have strained existing water infrastructure, leaving many residents dependent on expensive private vendors.

The northern regions experience severe drought effects on Nigerian water supply, while southern areas grapple with pollution from industrial activities. Climate change exacerbates these challenges, altering rainfall patterns and reducing groundwater levels in states like Kano and Sokoto.

This complex crisis stems from multiple factors, including inadequate investment and poor management, which we’ll explore further in the next section. Understanding these root causes is crucial for developing sustainable solutions to Nigeria’s water stress.

Key Statistics

Definition and Overview of Water Scarcity

Nigeria faces a growing water crisis with over 60 million people lacking access to clean water despite the country’s abundant freshwater resources.

Water scarcity occurs when demand exceeds available supply, creating physical shortages or limiting access due to infrastructure failures, as seen in Nigeria where 60 million lack clean water despite abundant resources. This crisis manifests differently across regions, from drought-induced shortages in northern states like Sokoto to pollution-ridden supplies in industrial southern cities like Port Harcourt.

The UN defines water stress when annual supply drops below 1,700 cubic meters per person, a threshold Nigeria approaches as its population grows while water sources diminish. Rapid urbanization exacerbates this pressure, with Lagos residents consuming just 25 liters daily—far below the 50-liter minimum standard—due to infrastructure gaps and groundwater depletion.

Understanding these dimensions of water scarcity sets the stage for examining Nigeria’s specific causes, from climate impacts to management failures, which we’ll analyze next. This systemic view helps explain why solutions must address both natural and human-made factors driving the crisis.

Major Causes of Water Scarcity in Nigeria

Water scarcity occurs when demand exceeds available supply creating physical shortages or limiting access due to infrastructure failures as seen in Nigeria where 60 million lack clean water despite abundant resources.

Nigeria’s water crisis stems from both environmental and systemic factors, including prolonged droughts in the north and pollution from oil spills in the Niger Delta, which have contaminated 70% of freshwater sources in affected areas. Climate change exacerbates these challenges, with erratic rainfall patterns reducing reservoir levels by 40% in states like Kano and Jigawa over the past decade.

Poor infrastructure compounds these issues, as 60% of urban water systems operate below capacity due to leakages and outdated pipelines, forcing Lagos residents to rely on costly private vendors. Weak governance further deepens the crisis, with only 10% of Nigeria’s water budget allocated to rural areas despite 80% of shortages occurring there, perpetuating inequality in access.

These interconnected causes—environmental degradation, failing infrastructure, and mismanagement—set the stage for examining how population growth intensifies demand, a critical factor we’ll explore next. Without addressing these root issues, Nigeria’s water stress will continue escalating alongside urbanization pressures.

Population Growth and Urbanization

Nigeria’s rapid population growth projected to reach 400 million by 2050 intensifies water demand while existing infrastructure struggles to keep pace worsening urban water scarcity in Lagos and other cities.

Nigeria’s rapid population growth, projected to reach 400 million by 2050, intensifies water demand while existing infrastructure struggles to keep pace, worsening urban water scarcity in Lagos and other cities. With urban populations growing at 4.3% annually, strained systems leave 60% of residents relying on informal vendors, paying up to 10 times more than piped water rates.

Rural-urban migration compounds the crisis as newcomers overwhelm already inadequate water networks, with Abuja’s water demand exceeding supply by 35% despite recent expansions. This imbalance forces households to exploit groundwater, accelerating depletion in northern states where aquifers are already receding by 1.5 meters yearly due to drought effects on Nigerian water supply.

As cities expand unchecked, poor planning further strains resources—a critical link to the next challenge: Nigeria’s decaying water infrastructure, which fails to meet even current needs. Without systemic upgrades, population pressures will render existing shortages unmanageable, deepening inequality between urban and rural water access problems in Nigeria.

Poor Infrastructure and Maintenance

Nigeria’s aging water infrastructure loses over 40% of treated water through leaks and pipe bursts with Lagos alone wasting 200 million liters daily due to dilapidated distribution networks.

Nigeria’s aging water infrastructure loses over 40% of treated water through leaks and pipe bursts, with Lagos alone wasting 200 million liters daily due to dilapidated distribution networks. This inefficiency exacerbates urban water scarcity in Lagos, forcing residents to spend 15% of their income on alternative sources despite government investments in treatment plants.

Northern states face collapsing boreholes and non-functional hand pumps, leaving 70% of rural water access problems in Nigeria unresolved due to poor maintenance budgets. The Federal Ministry of Water Resources reports that only 30% of Nigeria’s 2,300 waterworks operate at full capacity, crippling supply to growing populations.

These systemic failures intersect with environmental pressures, setting the stage for climate change impacts on Nigeria’s already stressed water resources. Without urgent rehabilitation, infrastructure decay will amplify drought effects on Nigerian water supply, particularly in groundwater-dependent northern regions.

Climate Change and Environmental Degradation

Nigeria allocates less than 0.5% of its annual budget to water infrastructure forcing states like Enugu to abandon 70% of borehole projects midway due to cost overruns.

Nigeria’s water crisis worsens as climate change reduces rainfall by 20-40% in northern regions since the 1970s, according to the Nigerian Meteorological Agency, while rising temperatures increase evaporation from already depleted reservoirs. Lake Chad, a critical water source for northeastern states, has shrunk 90% since the 1960s due to climate shifts and overuse, displacing millions dependent on its resources.

Deforestation in southern Nigeria accelerates soil erosion and reduces groundwater recharge rates, with Cross River State losing 161,000 hectares of forest between 2001-2020, worsening water scarcity during dry seasons. Unregulated sand mining in riverbeds, particularly along the Niger and Benue basins, further disrupts natural water storage and flow patterns, compounding supply challenges.

These environmental pressures interact with Nigeria’s crumbling infrastructure, creating a vicious cycle where climate extremes strain systems already losing 40% of treated water through leaks. The next section examines how inefficient water management policies fail to address these interconnected crises.

Inefficient Water Management Policies

Nigeria’s outdated water governance framework exacerbates scarcity, with 11 different federal agencies managing overlapping responsibilities yet failing to coordinate responses to climate-induced shortages. The National Water Resources Bill, stalled since 2017, could modernize allocation systems but remains unimplemented despite worsening drought conditions in northern states like Sokoto and Yobe.

State water boards lose ₦112 billion annually through non-revenue water—a combination of leaks and illegal connections—while only 10% of urban households receive piped water daily, according to UNICEF’s 2022 WASH report. This mismanagement disproportionately affects cities like Lagos, where 60% of residents rely on expensive private vendors despite the state spending ₦78 billion on water projects between 2015-2020.

Policies favoring large dams over localized solutions ignore groundwater depletion patterns, with borehole drilling increasing by 300% in Abuja since 2015 while aquifer levels drop 2 meters yearly. These systemic failures set the stage for examining how communities bear the brunt of scarcity through health crises and economic losses.

Impact of Water Scarcity on Nigerian Communities

Northern farming communities like those in Katsina now experience 40% crop yield reductions due to irrigation shortages, forcing 58% of households to spend over 30% of their income on water truck deliveries according to 2023 NBS data. This economic strain compounds existing poverty cycles, particularly in drought-prone regions where women and children spend 4-6 hours daily fetching water from contaminated sources.

Lagos slums illustrate urban consequences, with Makoko residents paying ₦500 per jerrycan—10 times the municipal rate—while enduring cholera outbreaks from untreated vendor supplies. The World Bank estimates such water stress costs Nigeria 5% of GDP annually through lost productivity and healthcare expenditures.

These community-level crises directly stem from the governance failures examined earlier, creating conditions where health vulnerabilities flourish. As we’ll explore next, contaminated water sources and poor sanitation trigger severe public health emergencies across demographic groups.

Health Implications of Water Scarcity

The reliance on contaminated water sources in Nigeria’s drought-prone regions has led to a 30% increase in waterborne diseases like cholera and dysentery, with UNICEF reporting over 100,000 child deaths annually linked to poor water quality. Women and children fetching water from polluted ponds face heightened risks of infections, exacerbating malnutrition and stunting in rural communities like Katsina.

Urban slums such as Makoko suffer recurrent cholera outbreaks, with Lagos recording 3,000 cases in 2023 alone due to untreated vendor water supplies. These health crises strain Nigeria’s healthcare system, consuming 12% of state health budgets for preventable water-related illnesses according to WHO data.

The resulting productivity losses from illness amplify poverty cycles, setting the stage for deeper economic consequences explored next.

Economic Consequences of Water Scarcity

Nigeria loses an estimated $1.3 billion annually in productivity due to water-related illnesses, with rural farmers in states like Jigawa experiencing 40% reduced crop yields from drought-induced water stress. The World Bank reports that urban businesses in Lagos spend 15% of operational costs on alternative water sources, squeezing profit margins in manufacturing and hospitality sectors.

Water scarcity forces households to allocate 20% of monthly income to water purchases, deepening poverty cycles in cities like Kano where informal vendors charge 10 times municipal rates. This economic strain disproportionately affects women-led microenterprises, with 60% reporting reduced working hours spent fetching water according to UNDP surveys.

The financial burden of water insecurity compounds Nigeria’s development challenges, setting the stage for examining its social and cultural ripple effects. These economic pressures reshape community dynamics, particularly in water-stressed regions where traditional livelihoods face extinction.

Social and Cultural Effects of Water Scarcity

The daily struggle for water reshapes social structures, with UNICEF reporting Nigerian women and girls spend 40 billion hours annually fetching water, disrupting education and community participation. In northern states like Katsina, early marriages increase as families prioritize reducing household water burdens over schooling for daughters.

Water scarcity erodes cultural practices tied to agriculture, with 65% of rural communities in Sokoto abandoning traditional irrigation festivals due to depleted groundwater. This loss of heritage compounds the economic strain discussed earlier, further marginalizing vulnerable groups.

These social fractures create tensions between urban and rural populations, particularly in Lagos where migration from water-stressed regions strains infrastructure. Such dynamics highlight the urgent need for solutions, setting the stage for examining current mitigation efforts.

Current Efforts to Address Water Scarcity in Nigeria

Amid growing water stress in Nigerian communities, NGOs like WaterAid Nigeria have installed over 50 solar-powered boreholes in Bauchi and Enugu states, reducing women’s water-fetching time by 60%. Private sector initiatives like the Lagos Water Corporation’s partnership with Veolia aim to upgrade aging infrastructure, though urban water scarcity persists due to rapid population growth.

In northern states facing groundwater depletion, the World Bank-backed Transforming Irrigation Management in Nigeria project has rehabilitated 1,200 hectares of irrigation schemes, reviving some abandoned agricultural traditions. However, rural water access problems remain acute, with only 30% of Sokoto’s villages having functional water points despite these interventions.

These mixed results highlight the need for coordinated policy action, setting the stage for examining government initiatives that could scale successful pilot projects nationwide. The next section explores how legislative frameworks and funding allocations might address systemic water shortage issues in Nigerian cities and countryside alike.

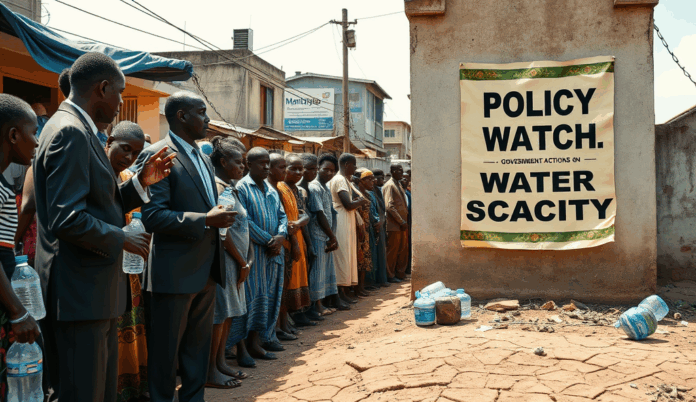

Government Initiatives and Policies

The Nigerian government has launched the National Water Resources Bill to standardize water management, though implementation lags in states like Sokoto where only 30% of villages have functional water points. Federal projects like the Partnership for Expanded Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (PEWASH) aim to replicate successful NGO interventions, targeting 100% rural water coverage by 2030 despite current groundwater depletion in northern regions.

Recent budget allocations show increased funding for urban water infrastructure, with Lagos receiving ₦28 billion for pipe network upgrades to complement private sector efforts like the Veolia partnership. However, rapid population growth continues outpacing these developments, leaving 60 million Nigerians without clean water access despite policy commitments.

These government actions set the foundation for NGO interventions, which often fill service gaps in underserved communities through localized solutions. The next section examines how organizations like WaterAid Nigeria scale impact where state programs fall short, particularly in rural areas facing acute water stress.

Role of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs)

NGOs like WaterAid Nigeria and the United Purpose have become critical in bridging water access gaps, particularly in rural areas where government programs struggle with implementation. These organizations deploy cost-effective solutions such as borehole installations and rainwater harvesting systems, reaching over 5 million Nigerians annually in states like Jigawa and Bauchi facing severe groundwater depletion.

Their localized approach often yields better sustainability than large-scale government projects, with community ownership models ensuring 75% functionality rates for water points compared to the national average of 50%. For instance, WaterAid’s collaboration with local leaders in Sokoto has maintained 200 functional water points since 2020, directly addressing the state’s 30% coverage deficit highlighted earlier.

As NGOs prove the viability of decentralized solutions, their innovations pave the way for community-led adaptations, which the next section explores in depth. These efforts demonstrate how grassroots interventions can complement policy frameworks while tackling immediate water stress in Nigeria’s most vulnerable regions.

Community-Based Solutions and Innovations

Building on NGO successes, Nigerian communities are developing low-cost innovations like sand filtration systems and water kiosks to combat urban water scarcity in Lagos and rural shortages. In Kano, local cooperatives have implemented pay-per-use solar pumps, increasing access for 15,000 residents while maintaining 90% operational rates through community maintenance funds.

These grassroots models address groundwater depletion in Northern Nigeria by combining traditional knowledge with modern technology, such as fog harvesting in Plateau State’s highlands. Women’s groups in Enugu now produce ceramic water filters from local clay, reducing diarrheal diseases by 40% in pilot communities while creating income streams.

Such community-led adaptations demonstrate how decentralized solutions can overcome inadequate water infrastructure in Nigeria, though scaling them faces systemic challenges explored next. These innovations prove that local ownership remains critical for sustainable water stress management across Nigerian communities.

Challenges in Solving Water Scarcity Issues

Despite promising grassroots innovations, systemic obstacles hinder Nigeria’s water stress solutions, including bureaucratic delays in approving community projects and inconsistent policy implementation across states. For instance, Lagos’ 2020 water masterplan remains partially executed due to inter-agency conflicts, leaving 60% of residents dependent on costly private vendors despite abundant surface water resources.

Climate variability exacerbates these challenges, with Northern Nigeria experiencing 30% reduced rainfall since 2010 while southern urban centers face saltwater intrusion contaminating 40% of coastal aquifers. Such environmental pressures strain decentralized systems like Kano’s solar pumps, requiring costly technical upgrades beyond most cooperatives’ capacities.

These multidimensional barriers reveal why scaling local solutions demands addressing deeper structural gaps, particularly funding shortages that cripple maintenance and expansion efforts nationwide. The next section examines how financial constraints perpetuate Nigeria’s water crisis despite available technical fixes.

Lack of Funding and Resources

Nigeria allocates less than 0.5% of its annual budget to water infrastructure, forcing states like Enugu to abandon 70% of borehole projects midway due to cost overruns. This chronic underfunding leaves functional waterworks like Abuja’s Lower Usuma Dam operating at 40% capacity despite serving 2 million residents.

The World Bank estimates Nigeria needs $10 billion annually to meet SDG6 targets, yet actual investments stagnate below $2 billion, worsening urban water scarcity in Lagos and other megacities. Rural communities face deeper crises, with 80% of Kano’s village water committees unable to afford spare parts for broken hand pumps.

These financial gaps intersect with earlier discussed climate pressures, as drought effects on Nigerian water supply demand expensive mitigation like desalination plants. Such underinvestment creates fertile ground for the corruption and mismanagement that plague subsequent project implementations.

Corruption and Mismanagement

Nigeria’s water scarcity crisis is exacerbated by systemic corruption, with the EFCC reporting $1.2 billion lost to fraudulent water contracts between 2015-2022. In Rivers State, 60% of allocated funds for water projects were diverted, leaving communities dependent on polluted streams.

Mismanagement compounds these issues, as seen in Lagos where 3 of 5 new treatment plants failed within a year due to improper maintenance. The National Water Resources Institute attributes 45% of project failures to unqualified contractors hired through nepotism.

These practices deepen urban water scarcity in Lagos and rural water access problems, setting the stage for public awareness gaps in holding officials accountable.

Public Awareness and Education Gaps

Compounding Nigeria’s water scarcity challenges, a 2022 UNICEF survey revealed only 38% of Nigerians understand their legal rights to clean water, enabling unchecked mismanagement. Many rural communities lack access to information about budget allocations, leaving them unaware when funds for projects like Rivers State’s diverted 60% disappear.

Urban populations face similar gaps, as Lagos residents often don’t realize failed treatment plants stem from contractor incompetence rather than natural shortages. The National Orientation Agency reports just 12% of Nigerians can identify reporting channels for water infrastructure complaints, perpetuating accountability failures.

Bridging these awareness gaps could empower citizens to demand transparency, creating pressure for reforms ahead of future mitigation strategies. Without grassroots education on water governance, even well-designed policies risk being undermined by persistent public disengagement.

Future Prospects for Mitigating Water Scarcity

Despite Nigeria’s persistent water governance challenges, emerging initiatives like the National Water Resources Bill offer legislative frameworks for equitable distribution, though implementation remains uneven across states. The World Bank projects that targeted investments in groundwater recharge systems could alleviate water stress for 40 million Nigerians by 2030, particularly in drought-prone northern regions where groundwater depletion exceeds 3 meters annually.

Lagos State’s recent partnership with private operators to upgrade aging treatment plants demonstrates how urban water scarcity can be addressed through blended financing models, though public oversight remains critical to prevent cost overruns. Satellite monitoring of reservoir levels in the Niger Delta, piloted by the Ministry of Water Resources, provides early warnings for shortages, enabling proactive responses to climate change impacts on water resources.

These technological and policy advancements must be coupled with the grassroots awareness campaigns discussed earlier to ensure communities can effectively participate in water governance. As we explore potential solutions in the next section, it’s clear that Nigeria’s water crisis requires both institutional reforms and localized adaptation strategies to achieve sustainable results.

Potential Solutions and Recommendations

Building on Nigeria’s emerging policy frameworks, scaling up groundwater recharge projects in northern states could mitigate drought effects on Nigerian water supply, particularly where depletion rates exceed 3 meters annually. The success of Lagos’ public-private partnerships for urban water scarcity should be replicated in other cities like Kano and Port Harcourt, with strict cost controls to prevent infrastructure overruns.

Satellite-based monitoring systems piloted in the Niger Delta should expand nationwide to address rural water access problems, integrating real-time data with community-led conservation efforts discussed earlier. The National Water Resources Bill must prioritize equitable implementation across states, ensuring climate change impacts on Nigerian water resources don’t exacerbate existing disparities between regions.

For sustainable results, Nigeria’s water crisis challenges require simultaneous investment in institutional capacity and localized solutions like rainwater harvesting in water-stressed communities. These multi-level approaches, combined with the technological advancements previously outlined, create a pathway toward resolving the country’s complex water stress dynamics as we reflect on key takeaways in the concluding section.

Conclusion on Water Scarcity in Nigeria

Nigeria’s water crisis persists due to a complex interplay of factors, from inadequate infrastructure in Lagos to groundwater depletion in Northern Nigeria, as explored in previous sections. Climate change exacerbates these challenges, with erratic rainfall patterns worsening drought effects on the national water supply.

Addressing urban water scarcity requires both immediate solutions like borehole regulation and long-term investments in pipe networks, particularly in high-density areas. Rural communities face distinct hurdles, where 60% lack clean water access despite Nigeria’s abundant freshwater resources.

Moving forward, coordinated efforts must tackle Nigeria’s water crisis challenges holistically, balancing urban needs with rural realities. The next steps involve examining policy frameworks that could transform water management nationwide, building on the foundations laid in this analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I protect my family from waterborne diseases during water scarcity in Nigeria?

Use ceramic water filters or boil water for 5 minutes to kill pathogens, and consider WaterAid Nigeria's community water projects for long-term solutions.

What practical steps can Lagos residents take to cope with urban water scarcity?

Install rainwater harvesting systems and report pipe leaks to LWC's toll-free line (0800-WATER-LAGOS) to improve municipal response times.

How can northern Nigerian farmers adapt to drought effects on water supply?

Practice drip irrigation and join the Transforming Irrigation Management project to access rehabilitated water schemes for sustainable farming.

Where can rural communities report water infrastructure failures in Nigeria?

Contact the National Water Resources Institute's hotline (08139887200) or use the WASHWatch Nigeria app to document and escalate service gaps.

What budget advocacy tools exist for improving water funding in Nigeria?

Use Tracka.ng to monitor local government water project allocations and attend town hall meetings to demand transparency in spending.