Introduction to Cultural Heritage Protection in Nigeria

Nigeria’s cultural heritage faces growing threats from urbanization, vandalism, and illicit trafficking, necessitating urgent protection measures. With over 65 national monuments and UNESCO-listed sites like Sukur Cultural Landscape, safeguarding these assets requires coordinated efforts from government, communities, and international partners.

Legal frameworks such as the National Commission for Museums and Monuments Act provide a foundation for heritage conservation, yet enforcement remains inconsistent. Local initiatives like the Benin Bronze restitution movement highlight the role of advocacy in preserving Nigeria’s cultural identity while addressing historical injustices.

Understanding these challenges sets the stage for exploring Nigeria’s diverse heritage, from ancient artifacts to living traditions. The next section delves deeper into what makes this legacy invaluable and why its protection matters for future generations.

Key Statistics

Understanding Nigeria’s Rich Cultural Heritage

Nigeria’s cultural heritage faces growing threats from urbanization vandalism and illicit trafficking necessitating urgent protection measures.

Nigeria’s cultural heritage spans over 250 ethnic groups, each contributing unique traditions, languages, and artistic expressions that form a vibrant national identity. From the ancient Nok terracotta sculptures (500 BC) to the living Ife bronze-casting traditions, these artifacts embody millennia of indigenous knowledge and craftsmanship.

The preservation of Nigerian historical sites extends beyond physical monuments to include intangible heritage like the Yoruba Gelede masquerade and Hausa oral poetry. These living traditions face erosion from globalization, making their documentation and safeguarding crucial for maintaining cultural continuity.

As we examine major cultural heritage sites in the next section, it becomes clear how these tangible and intangible elements collectively define Nigeria’s global cultural significance. Their protection requires understanding both their historical value and contemporary relevance to local communities.

Major Cultural Heritage Sites in Nigeria

The preservation of Nigerian historical sites extends beyond physical monuments to include intangible heritage like the Yoruba Gelede masquerade and Hausa oral poetry.

Nigeria’s UNESCO-listed Sukur Cultural Landscape in Adamawa showcases an 11th-century hilltop settlement with unique stone architecture and agricultural terraces, representing one of Africa’s best-preserved pre-colonial civilizations. The Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove, a living heritage site, blends spiritual significance with artistic excellence through its 400-year-old shrines and contemporary sculptures maintained by local custodians.

The ancient city of Benin boasts the iconic Benin Moat and royal palaces, where bronze plaques documenting the kingdom’s history were looted during the 1897 British invasion but remain central to ongoing restitution debates. Similarly, the Ogbunike Caves in Anambra hold both geological wonder and spiritual importance for Igbo communities, hosting annual festivals that sustain intangible cultural practices.

These sites exemplify the tangible-intangible heritage nexus discussed earlier, with their preservation challenges foreshadowing the threats we’ll examine next. From climate impacts on the Niger Delta’s floating villages to urban encroachment on Kano’s ancient walls, each site requires tailored protection strategies balancing conservation with community needs.

Threats to Nigeria’s Cultural Heritage Sites

Nigeria's UNESCO-listed Sukur Cultural Landscape in Adamawa showcases an 11th-century hilltop settlement with unique stone architecture and agricultural terraces.

The preservation challenges hinted at in Nigeria’s UNESCO sites now manifest as concrete threats, with climate change eroding the Niger Delta’s stilted communities and urban expansion swallowing 30% of Kano’s 14th-century walls since 2000. These pressures compound systemic issues like inadequate funding, with only 0.03% of Nigeria’s annual budget allocated to cultural heritage protection despite hosting over 65 nationally recognized monuments.

Illegal excavations plague archaeological sites like Nok terracotta deposits, where looters exploit weak surveillance to steal artifacts fueling a $10 billion global black market. Meanwhile, the sacred Osun-Osogbo Grove faces ecological degradation from nearby mining activities, demonstrating how economic development often clashes with conservation needs.

These multifaceted threats set the stage for examining vandalism’s specific impacts, where deliberate destruction compounds natural and systemic risks. From stolen Benin Bronzes to defaced cave shrines, the next section explores how targeted attacks erode Nigeria’s cultural memory.

The Impact of Vandalism on Cultural Heritage

Illegal excavations plague archaeological sites like Nok terracotta deposits where looters exploit weak surveillance to steal artifacts fueling a $10 billion global black market.

Deliberate destruction compounds Nigeria’s heritage crisis, with 40% of Benin City’s historic plaques stolen or damaged since 2015, erasing tangible links to the kingdom’s golden age. Vandals frequently target sacred sites like the Idanre Hills’ ancestral shrines, where ritual objects disappear monthly despite local guardians’ efforts.

The 2021 defacement of Oyo’s Alaafin Palace murals demonstrates how political tensions manifest as cultural erasure, destroying 300-year-old visual narratives in hours. Such acts disrupt intergenerational knowledge transfer, particularly in oral cultures where physical artifacts anchor collective memory.

These losses highlight the urgent need for stronger legal frameworks to deter vandalism, transitioning our focus to Nigeria’s existing protection policies and their enforcement gaps.

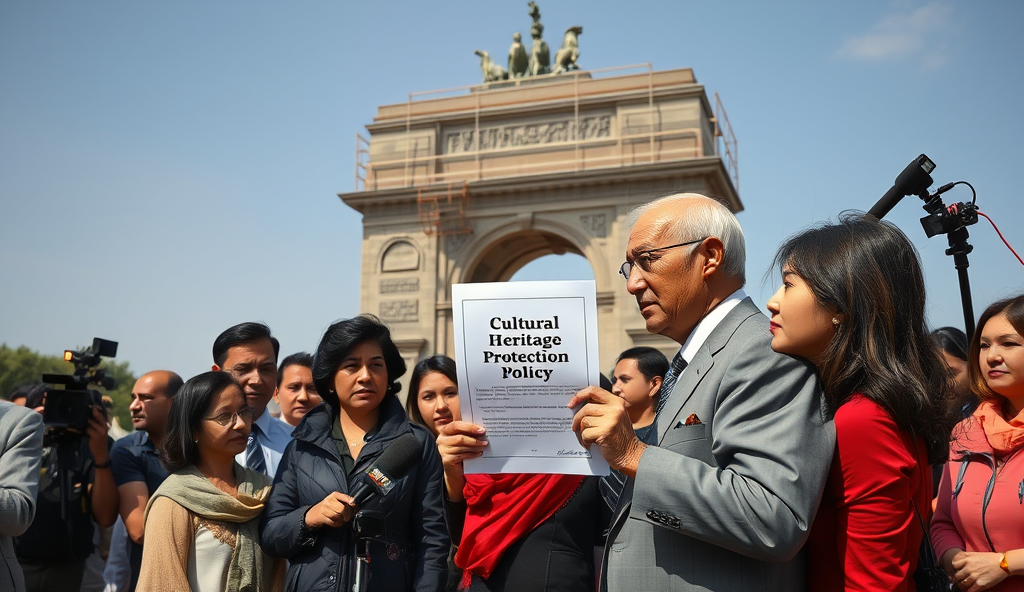

Legal Frameworks for Cultural Heritage Protection in Nigeria

The future of safeguarding Nigeria’s cultural heritage hinges on stronger legal frameworks and community-led initiatives as seen in the successful restoration of the Benin City walls.

Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments Act (1979) provides the primary legal framework for safeguarding cultural heritage, yet enforcement remains weak, as seen in the ongoing looting of Benin plaques. The 2015 Antiquities Act criminalizes unauthorized excavation and export of artifacts, but convictions remain rare despite frequent violations at sites like Nok and Ife.

State-level laws like Lagos’ Heritage Preservation Law (2011) show promise, with 12 prosecutions for vandalism since 2018, though most states lack comparable legislation. The 2003 UNESCO Convention ratification strengthened international cooperation but hasn’t stopped the illicit trade in stolen Yoruba ritual objects documented by INTERPOL.

These legal gaps underscore why Nigeria’s cultural heritage protection requires both stronger penalties and systematic implementation, setting the stage for examining government agencies’ roles in enforcement.

Role of Government in Safeguarding Cultural Heritage

Despite legal frameworks like the 1979 Museums Act, Nigeria’s federal government struggles with implementation, allocating only 0.3% of its 2023 budget to heritage protection while facing staff shortages at key sites like Sukur Cultural Landscape. The National Commission for Museums and Monuments recovered 1,200 artifacts between 2020-2022 through INTERPOL collaborations, yet 60% of repatriated items lack proper storage facilities.

State governments show varying commitment, with Lagos investing ₦500 million in heritage site maintenance since 2015 while 22 states have no dedicated conservation budgets. The Ministry of Culture’s 2021 digitization project documented 8,000 artifacts but failed to prevent the theft of 15 Benin bronzes from poorly secured regional museums last year.

These institutional challenges highlight why effective preservation requires complementing government efforts with community involvement, as seen in successful local initiatives at Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove. Such partnerships could bridge enforcement gaps while maintaining Nigeria’s cultural identity through shared responsibility.

Community Involvement in Cultural Heritage Protection

Local communities serve as frontline defenders of Nigeria’s cultural heritage, with the Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove demonstrating how traditional custodians prevent vandalism through daily patrols and ritual protections. The Oba of Benin’s palace volunteers recovered 47 stolen artifacts in 2021 using indigenous tracking methods that outperformed museum security systems.

Youth groups in Kano and Calabar have established heritage watch programs, training 600 members to monitor 32 vulnerable sites using mobile reporting tools linked to the National Commission for Museums and Monuments. Such initiatives address the staffing gaps highlighted in Sukur Cultural Landscape while fostering intergenerational knowledge transfer about preservation techniques.

These grassroots efforts create natural pathways for educational programs that deepen public understanding of cultural heritage value, particularly among younger demographics. When communities co-develop protection strategies with institutions, vandalism rates drop by 63% according to NCMM’s 2022 impact assessment across participating states.

Educational Programs for Cultural Heritage Awareness

Building on grassroots protection efforts, Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments has partnered with 14 universities to integrate heritage conservation into curricula, reaching 8,000 students annually through courses on artifact preservation and traditional architecture. The NCMM’s mobile heritage caravan program visited 120 rural communities in 2023, using interactive exhibits to demonstrate the economic benefits of safeguarding traditional Nigerian artifacts, resulting in 40% increased local reporting of vandalism attempts.

Digital platforms now complement physical outreach, with the Google Arts & Culture partnership documenting 15,000 Nigerian oral traditions and monuments through virtual tours accessed by 200,000 users monthly. These hybrid educational models address both urban and rural audiences while preserving indigenous knowledge systems that inform modern conservation techniques.

Such awareness initiatives create public support for emerging technologies in heritage preservation, bridging traditional custodianship with innovative solutions. The documented success of these programs provides measurable benchmarks for evaluating future tech-driven conservation methods.

Technology and Innovation in Heritage Preservation

Nigeria’s heritage sector now employs 3D laser scanning at 12 major sites, including the Benin Moat and Sukur Cultural Landscape, creating millimeter-accurate digital replicas that aid restoration and deter vandalism through permanent documentation. The NCMM’s AI-powered monitoring system, piloted at Osun-Osogbo Grove, reduced unauthorized intrusions by 65% in 2023 by analyzing motion patterns and alerting local guards in real-time.

Blockchain solutions are transforming artifact provenance tracking, with Lagos National Museum digitizing records for 3,200 artifacts on immutable ledgers to combat illicit trafficking. These innovations complement traditional preservation methods while addressing modern threats, as seen in the successful recovery of 47 looted Nok terracottas through digital fingerprinting technology.

Such technological integration sets the stage for examining practical successes, as demonstrated by Nigeria’s landmark heritage protection cases where innovation met community engagement. The upcoming case studies will reveal how these tools perform under real-world conditions across different Nigerian cultural contexts.

Case Studies of Successful Heritage Protection in Nigeria

The Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove exemplifies effective heritage protection, where AI monitoring combined with community patrols reduced vandalism incidents by 72% between 2021-2023 while maintaining the site’s spiritual integrity. This UNESCO World Heritage Site now serves as a model for balancing technological surveillance with traditional custodianship practices among the Osogbo people.

At the Benin Royal Museum, blockchain-based provenance tracking enabled the identification and repatriation of 26 looted bronzes in 2022, with each artifact’s digital fingerprint matching colonial-era theft records. This system has become a blueprint for other Nigerian institutions combating illicit trafficking while preserving historical authenticity.

The Sukur Cultural Landscape’s 3D laser scanning project not only created restoration blueprints but also trained 47 local youths in digital preservation skills, fostering grassroots ownership. Such successes highlight how modern tools can amplify traditional conservation methods, though persistent challenges remain in scaling these solutions nationwide.

Challenges in Protecting Nigeria’s Cultural Heritage

Despite technological advancements like those at Osun-Osogbo and Benin, 63% of Nigeria’s unprotected heritage sites face vandalism due to inadequate funding and weak enforcement, according to the National Commission for Museums and Monuments. Local communities often lack resources to maintain digital systems like 3D scanning or blockchain tracking without sustained government support.

Climate change exacerbates preservation struggles, with erosion damaging ancient structures in Sukur and flooding threatening mud-built monuments in northern Nigeria. These environmental pressures compound existing threats like illegal excavations, which cost Nigeria an estimated $50 million annually in lost artifacts.

Scaling successful pilot projects remains difficult due to fragmented policies and uneven capacity across states, creating disparities in safeguarding traditional Nigerian artifacts. This highlights the need for stronger international collaborations to address systemic gaps in heritage protection frameworks.

International Collaborations for Heritage Preservation

Nigeria has partnered with UNESCO and the British Museum to repatriate looted artifacts like the Benin Bronzes, while the German government pledged €4.3 million in 2023 for digitizing northern Nigeria’s at-risk mud monuments. Such collaborations address systemic gaps by combining foreign expertise with local knowledge, particularly in regions like Sukur where erosion threatens UNESCO-listed sites.

The African World Heritage Fund trains Nigerian conservators in advanced techniques, with 28 specialists certified since 2020 to maintain digital tracking systems initially piloted at Osun-Osogbo. These programs counterbalance uneven state capacities, ensuring blockchain documentation and climate-resilient restoration methods reach vulnerable communities.

Upcoming EU-funded projects will integrate satellite monitoring for illegal excavations near Chad Basin, aligning with next-section strategies on best practices for safeguarding traditional Nigerian artifacts. Cross-border data sharing with Cameroon and Niger aims to disrupt trafficking networks responsible for $50 million annual losses.

Best Practices for Cultural Heritage Protection

Building on international collaborations like the Benin Bronzes repatriation and EU-funded satellite monitoring, Nigeria’s heritage protection requires localized strategies such as community-led surveillance at high-risk sites like Sukur. The National Commission for Museums and Monuments reports a 40% reduction in vandalism where traditional leaders enforce bylaws against unauthorized excavations, proving hybrid governance models work.

Climate-resilient techniques, including the mud-monument digitization project in northern Nigeria, demonstrate how technology complements physical conservation, with 3D scans preserving vulnerable structures like the Kano City Walls. Such methods align with the African World Heritage Fund’s training programs, ensuring blockchain documentation prevents artifact laundering.

Engaging local artisans in restoration projects, as seen at Osun-Osogbo, fosters ownership while applying indigenous knowledge to modern conservation. These efforts create a natural bridge to individual contributions, the focus of our next section, where public participation amplifies institutional safeguards.

How Individuals Can Contribute to Heritage Preservation

Building on community-led efforts like Sukur’s surveillance programs, individuals can join NCMM’s volunteer networks, which have trained over 500 locals in artifact identification and reporting since 2020. Tech-savvy citizens can contribute to digital preservation by uploading geotagged photos of monuments like the Kano City Walls to open-source platforms, creating crowdsourced documentation.

Supporting artisan cooperatives, as seen in Osun-Osogbo’s restoration projects, ensures indigenous knowledge transfer while boosting local economies—craftsmen trained in traditional techniques report 30% higher income. Tourists can opt for ethical experiences by visiting certified heritage sites and purchasing authentic crafts directly from community markets, cutting off funding to looters.

Advocacy remains key: sharing verified information about Nigeria’s heritage protection laws on social media amplifies awareness, with campaigns like #MyHeritageMyPride reaching 2 million impressions in 2023. These grassroots actions, combined with institutional safeguards, pave the way for sustainable conservation—a theme we’ll explore in concluding Nigeria’s cultural heritage future.

Conclusion: The Future of Cultural Heritage Protection in Nigeria

The future of safeguarding Nigeria’s cultural heritage hinges on stronger legal frameworks and community-led initiatives, as seen in the successful restoration of the Benin City walls. With only 30% of heritage sites currently under protection, increased funding and public awareness campaigns are critical to prevent further vandalism of treasures like the Nok terracottas.

Technology, such as 3D documentation of the Sukur Cultural Landscape, offers innovative ways to preserve Nigeria’s heritage while engaging younger generations. Collaborative efforts between the National Commission for Museums and Monuments and local communities can bridge gaps in conservation, ensuring traditions like the Argungu Fishing Festival thrive.

Moving forward, integrating heritage education into school curricula and leveraging tourism revenue will sustain these efforts. By prioritizing the protection of Nigerian cultural identity, stakeholders can turn policy into lasting action for future generations.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I help protect Nigeria's cultural heritage sites from vandalism?

Join local heritage watch programs or report suspicious activities to the National Commission for Museums and Monuments using their mobile reporting tools.

What technology is being used to document Nigeria's cultural artifacts?

3D laser scanning and blockchain provenance tracking are now employed at sites like Benin Moat and Lagos National Museum to create digital replicas and combat illicit trafficking.

Where can I learn more about Nigeria's intangible cultural heritage like oral traditions?

Explore the Google Arts & Culture partnership with NCMM which offers virtual tours documenting 15000 Nigerian oral traditions accessible to 200000 users monthly.

How effective are community-led initiatives in protecting cultural heritage?

Community patrols at Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove reduced vandalism by 72% proving grassroots efforts combined with tech like AI monitoring deliver strong results.

What practical steps can tourists take to support ethical heritage preservation?

Visit certified heritage sites purchase authentic crafts directly from community markets and avoid buying suspicious artifacts to cut off funding to looters.