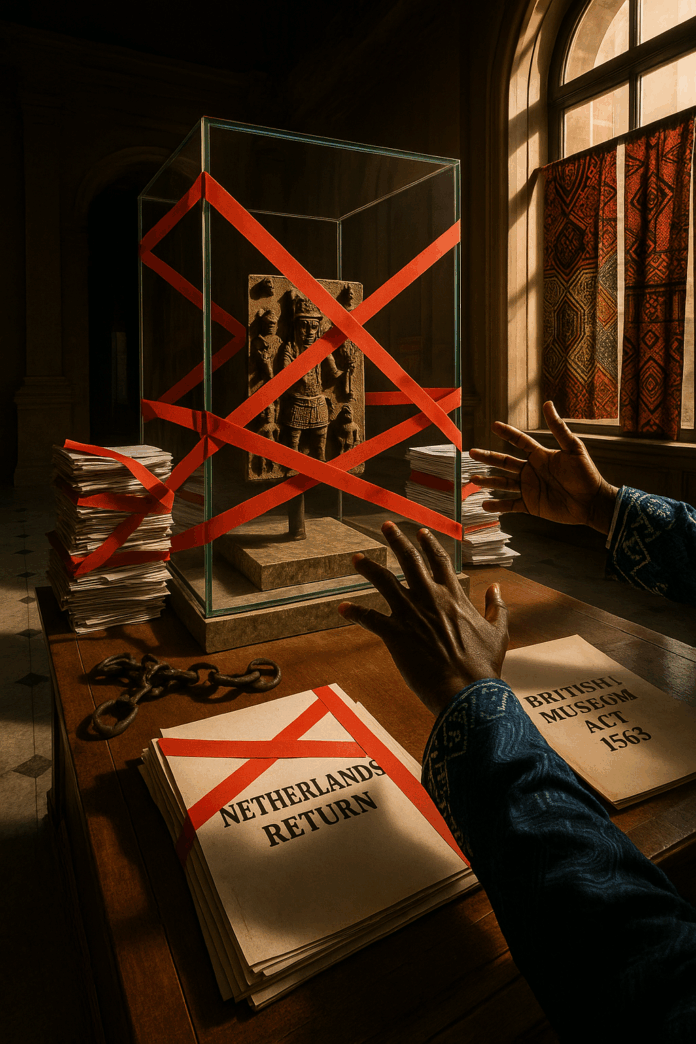

The air in Lagos crackled with ceremonial energy on June 21, 2025, as Dutch officials handed 119 Benin Bronzes – intricate plaques, regalia, and sculptures – to Nigerian custodians. This historic transfer, the largest single physical repatriation to date, represented a hard-won victory after 128 years in exile. Netherlands Ambassador Dewi van de Weerd called it “the foundation for further cooperation,” while Nigeria’s museum director Olugbile Holloway hailed its symbolism for “the pride and dignity of not just the Benin people, but the whole of Nigeria”. Yet behind this triumph lies an uncomfortable truth: thousands more Bronzes remain imprisoned in Western institutions, entangled in legal red tape, political maneuvering, and logistical quagmires. Even as Germany pledges to return 1,000+ pieces and the Smithsonian prepares its October 2025 handover, the British Museum alone retains approximately 928 pieces, citing legal restrictions. These cultural heritage restitution delays reveal a painful paradox: moral consensus has shifted, but systemic inertia perpetuates colonial-era injustice.

The 1897 Wound: Scars of Imperial Plunder

The Benin Bronzes’ tragedy begins with fire and blood. In February 1897, British forces launched a “punitive expedition” against the Kingdom of Benin after a trade delegation’s ambush. Approximately 1,200 troops under Admiral Sir Harry Rawson razed Benin City, massacring thousands, blowing up sacred sites, and deposing Oba Ovonramwen. The subsequent looting wasn’t opportunistic; it was systematic military policy. Soldiers ransacked the royal palace, seizing 3,000–5,000 artifacts – brass plaques, ivory leopards, commemorative heads – to auction for £40,000 (roughly £5 million today) to fund the invasion.

These weren’t mere trophies. As artist Enotie Ogbebor explains: “They are evidence of an organized society… the very pedestal which our ancestors built for us to expand on”. Crafted by Edo guilds since the 16th century, the Bronzes functioned as historical archives, spiritual conduits, and dynastic legacies. One ceremonial cockerel, for instance, honored past Obas’ wisdom; plaques depicted Portuguese traders and royal ceremonies. Their violent removal severed a living cultural lineage. By 1900, looted pieces flooded European markets, dispersing to 130+ institutions across 20 countries – from Berlin’s Ethnological Museum (1,130 items) to Cambridge University (116 pieces). Nigeria’s independence in 1960 ignited repatriation campaigns, but decades of pleas met silence or legalistic rebuttals.

The Bureaucratic Quagmire: Why Returns Stall

Institutional Hesitation & Legal Armor

While the Netherlands’ unconditional return sets a benchmark, major holders deploy creative obstruction. The British Museum epitomizes this, citing the British Museum Act 1963 – which prohibits deaccessioning – to justify retaining its 928 Bronzes. Instead, it offers “loans,” framing itself as a “library of the world” promoting “pluralism”. Critics like Oxford professor Dan Hicks condemn this as “an enduring brutality refreshed every day”. Smaller institutions hide behind endless “due diligence”: provenance research, conservation assessments, and insurance logistics. Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie Bunch III admitted their systems were “not set up for this,” despite ethical commitment.

Nigeria’s Custody Conundrum

A 2023 Nigerian presidential decree declared the Oba of Benin the “sole owner and custodian” of all returned Bronzes. This clashed violently with the National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM), the federal body with climate-controlled storage and curatorial expertise. When Cambridge paused its 2023 repatriation over recipient uncertainty, the diplomatic fallout was severe. Resolution came only in February 2025: the Oba granted NCMM authority to “display, conserve and pursue reparation” while his Benin Royal Museum is built. Yet this détente remains fragile, as Edo State’s governor still pushes for federal control at the rival Edo Museum of West African Art.

Logistical Labyrinths

Physical returns demand Herculean coordination. The Wereldmuseum’s repatriation required months of labor: artifacts wrapped in specialty paper, packed in custom crates, and secured for transport. Smaller institutions lack resources for such projects, while others fear liability for damage. As Professor Jürgen Zimmerer notes: “Colonialism was a European project… All of the global North are implicated” – yet no centralized system exists to streamline returns.

Stakeholder Voices: Frustration, Hope, and Defiance

Nigerian Leadership

Olugbile Holloway (NCMM Director) states bluntly: “The return is about the dignity of our people and undoing the injustice of 1897”. He praises the Smithsonian’s partnership model but implicitly critiques the British Museum’s delays: “We ask the world to treat us with fairness, dignity and respect”. Oba Ewuare II hails restitutions as “divine intervention,” insisting the Royal Museum within his palace is the only “legitimate destination”.

Western Institutions

Pro-restitution museums like the Smithsonian and Wereldmuseum acknowledge bureaucratic hurdles but prioritize ethical action. Wereldmuseum Director Marieke van Bommel stated bluntly: “These don’t belong here. They were violently taken, so they need to go back”. Hesitant holders like the British Museum defend retention using “cultural internationalism” – arguing global access trumps national ownership.

Scholars & Cultural Commentators

Phillip Ihenacho (Edo Museum Director) condemns Western media for framing Nigeria as “chaotic,” urging focus on rebuilding cultural infrastructure: “We must ensure ‘restitution’ is shaped by us, not just about victimhood”. Jürgen Zimmerer (Historian) observes: “Germany handled restitution poorly… Bureaucracy masks ongoing power imbalances”.

Pathways Forward: Blueprints to Break the Logjam

Unified Custody & Infrastructure in Nigeria

The February 2025 NCMM-Oba agreement is critical. With custody clarified, Nigeria must accelerate the Benin Royal Museum’s construction, funded by international partners (e.g., Germany pledged €4 million). This ensures artifacts aren’t “orphaned” upon return.

Adopting Proven Restitution Models

The “Smithsonian Model” offers a compelling template: full ownership transfer to Nigeria combined with long-term loans to Western museums plus joint research/curatorship. This balances ethics with “global access” concerns. The Dutch/German approach demonstrates how government-to-government agreements can bypass museum-level resistance. The Netherlands’ unconditional return sets a powerful precedent.

Legal & Policy Reform

Amending or circumventing laws like the British Museum Act 1963 remains essential. Labour Party leader Keir Starmer has pledged to review this if elected. Creating EU/US taskforces to standardize restitution procedures would reduce ad-hoc negotiations.

Digital & Collaborative Stewardship

Launching a global digital archive of Benin artifacts enables virtual reunification while physical returns progress. Nigerian institutions already collaborate with Digital Benin – this must expand to include all holding institutions.

Beyond Delays – Toward Justice and Renewed Creation

Cultural heritage restitution delays are more than administrative headaches; they are open wounds. Each day the Bronzes remain scattered, the 1897 violence echoes – a point Ogbebor articulates wrenchingly: “They speak to our DNA… colonialism dictated our past, but the Bronzes can redefine our future”. Yet momentum is building. The Netherlands’ return proves bureaucratic barriers can be dismantled. Germany’s pending return of 1,000+ Bronzes signals seismic shifts.

True restitution, however, transcends physical transfers. As Phillip Ihenacho argues, it requires rebuilding Benin City’s creative ecosystem: supporting young artists, curators, and guilds – much like the Oba’s historic patronage. When contemporary Edo artists exhibit alongside repatriated Bronzes, colonial theft transforms into living creativity.

The Bronzes’ homecoming is not charity; it is justice. And justice delayed, as Martin Luther King Jr. warned, is justice denied. Let 2025 be remembered not for the delays that linger, but for the dawn they finally began to crack.