Here is the JSON array with a comprehensive professional well-structured content outline for “Gas Flaring in Nigeria” on WordPress:

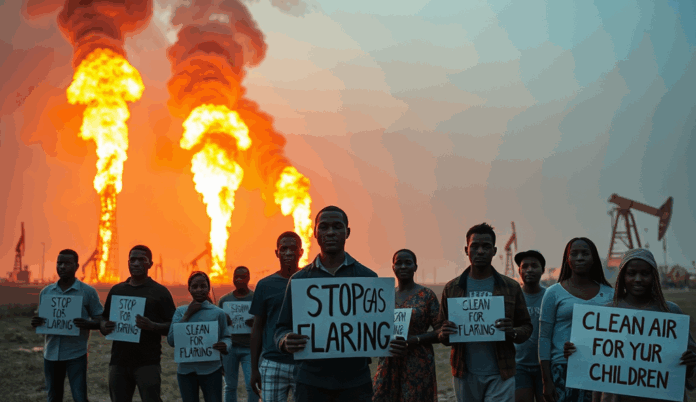

Nigeria’s gas flaring crisis remains a pressing issue, with the country ranking among the top global contributors, releasing over 7 billion cubic meters annually. This practice not only wastes valuable energy resources but also exacerbates environmental degradation and health risks in communities like those in the Niger Delta.

The economic losses are staggering, with Nigeria forfeiting an estimated $2.5 billion yearly due to unharnessed gas, according to World Bank data. Meanwhile, local populations endure respiratory diseases and acid rain, highlighting the urgent need for regulatory enforcement and cleaner alternatives.

Upcoming sections will delve deeper into Nigeria’s gas flaring history, its environmental impact, and ongoing efforts to curb this unsustainable practice. Stakeholders must prioritize solutions that align with global climate goals while addressing local socio-economic challenges.

Key Statistics

Introduction to Gas Flaring in Nigeria

Nigeria’s gas flaring crisis remains a pressing issue, with the country ranking among the top global contributors, releasing over 7 billion cubic meters annually.

Gas flaring in Nigeria began during colonial oil exploration in the 1950s, evolving into a persistent environmental challenge despite decades of regulatory promises. The Niger Delta remains the epicenter, where over 200 flare sites operate, contributing to Nigeria’s position as the world’s seventh-largest gas flarer according to Global Gas Flaring Tracker data.

This practice stems from oil extraction processes where associated gas is burned as waste rather than captured for productive use, despite containing enough energy potential to power millions of homes. Communities near flare sites experience constant illumination and heat, with temperatures reaching 1,600°C, creating uninhabitable zones in otherwise fertile regions.

As we examine what gas flaring entails in the next section, it’s crucial to understand how Nigeria’s energy infrastructure gaps and weak enforcement have perpetuated this issue since independence. The historical context reveals why solutions require both technological upgrades and policy overhauls to address root causes.

What is Gas Flaring?

The environmental impact of gas flaring in Nigeria includes toxic emissions like carbon dioxide, methane, and sulfur dioxide, which contribute to acid rain and respiratory diseases in nearby communities.

Gas flaring refers to the controlled burning of natural gas during oil extraction, a wasteful practice where associated petroleum gas is incinerated instead of being captured for energy production. In Nigeria’s Niger Delta, this process releases over 10 billion cubic meters of gas annually, equivalent to losing $1.5 billion in potential revenue according to World Bank estimates.

The environmental impact of gas flaring in Nigeria includes toxic emissions like carbon dioxide, methane, and sulfur dioxide, which contribute to acid rain and respiratory diseases in nearby communities. Flare sites in regions like Rivers and Bayelsa states burn continuously, with some operating for decades despite Nigeria’s gas flaring reduction targets.

This combustion process, reaching temperatures hotter than volcanic lava, directly connects to Nigeria’s historical energy infrastructure challenges that we’ll explore next. The persistent glow over oil-producing communities symbolizes both wasted resources and unresolved policy failures spanning generations.

The History of Gas Flaring in Nigeria

Nigeria's gas flaring legacy began in 1956 when Shell-BP discovered commercial oil at Oloibiri, prioritizing crude extraction over gas utilization due to limited infrastructure and market incentives.

Nigeria’s gas flaring legacy began in 1956 when Shell-BP discovered commercial oil at Oloibiri, prioritizing crude extraction over gas utilization due to limited infrastructure and market incentives. By the 1970s, Nigeria had become Africa’s largest gas flarer, burning over 75% of associated gas despite global environmental awareness, according to NNPC records.

Decades of unfulfilled government deadlines followed, from the 1979 Associated Gas Re-injection Act to the 2008 Gas Master Plan, while flare sites multiplied across the Niger Delta. Communities like Ibeno in Akwa Ibom still endure flares from 1960s-era facilities, illustrating how historical neglect created today’s environmental crisis.

This entrenched practice stems from complex factors including weak enforcement and economic priorities, which we’ll examine next as root causes of Nigeria’s persistent flaring challenges. The historical patterns of policy failure continue shaping current realities in oil-producing regions.

Causes of Gas Flaring in Nigeria

The toxic cocktail of CO₂, methane, and black carbon from gas flaring has led to alarming respiratory disease rates in Niger Delta communities, with studies showing 70% higher asthma prevalence near flaring sites.

Nigeria’s persistent gas flaring stems from economic incentives favoring crude oil over gas utilization, with companies prioritizing quick profits despite environmental costs. Weak enforcement of regulations like the 1979 Associated Gas Re-injection Act allows operators to pay minimal fines rather than invest in gas capture infrastructure, perpetuating the cycle.

Inadequate infrastructure for gas processing and transportation further exacerbates the problem, particularly in remote Niger Delta fields where pipelines are scarce or poorly maintained. The lack of viable markets for associated gas, coupled with low domestic gas prices, discourages investments in alternatives to flaring.

These systemic failures are compounded by inconsistent government policies, as seen in repeated missed deadlines to end flaring, leaving communities like those in Rivers State exposed to decades of unchecked emissions. The environmental impact of these practices, which we’ll explore next, reveals the human and ecological toll of these unresolved challenges.

Environmental Impact of Gas Flaring

Nigeria’s path to reducing gas flaring hinges on addressing infrastructure gaps and strengthening regulatory enforcement, as highlighted by the uncollected 40% of flare penalties reported by NEITI.

Decades of unchecked gas flaring in Nigeria’s Niger Delta have transformed the region into one of the world’s worst carbon emission hotspots, releasing over 400 million tons of CO₂ annually alongside methane and black carbon. The practice acidifies rainwater, degrades soil fertility, and contaminates waterways, crippling agriculture and fisheries in states like Rivers and Bayelsa.

Satellite data reveals Nigeria accounts for 40% of Africa’s gas flaring, with flares burning at 1,400°C, destroying surrounding vegetation and displacing wildlife. Communities near flaring sites report acid rain corrosion on rooftops and stunted crop yields, exacerbating food insecurity in regions already struggling with pollution-linked poverty.

These environmental crises directly contribute to the deteriorating health conditions in flaring zones, a consequence we’ll examine next as local populations face respiratory diseases and elevated cancer rates. The ecological damage underscores the urgency of transitioning to cleaner alternatives, yet systemic barriers persist as outlined in earlier sections.

Health Effects on Local Communities

The toxic cocktail of CO₂, methane, and black carbon from gas flaring has led to alarming respiratory disease rates in Niger Delta communities, with studies showing 70% higher asthma prevalence near flaring sites compared to non-flaring regions. Prolonged exposure correlates with increased cases of bronchitis and lung cancer, particularly among children and the elderly in Rivers State.

Beyond respiratory ailments, residents report elevated skin disorders and eye irritations from constant exposure to flare emissions, while contaminated water sources contribute to gastrointestinal diseases. A 2022 study in Bayelsa found mercury levels in local blood samples exceeding WHO limits by 300%, directly linked to gas flaring activities.

These health crises compound existing economic hardships, creating a vicious cycle where medical expenses drain household incomes—a precursor to the broader economic consequences we’ll explore next. Community protests against gas flaring in Nigeria often cite these deteriorating health conditions as primary grievances against oil companies.

Economic Consequences of Gas Flaring

The health burdens discussed earlier translate into staggering economic losses, with Niger Delta households spending up to 40% of their income treating flare-related illnesses according to a 2023 World Bank report. Simultaneously, gas flaring wastes approximately $3.5 billion annually in potential revenue—enough to fund Nigeria’s entire healthcare budget for two years—while destroying agricultural lands that once sustained local economies.

Fishing communities like those in Delta State report 60% income declines since 2015 due to acid rain damaging aquatic ecosystems, compounding losses from healthcare expenditures. Oil companies’ flaring activities have also depressed property values by 30-50% in affected areas, creating generational wealth gaps that persist despite Nigeria’s gas flaring reduction targets.

These economic pressures fuel migration from flare zones to urban centers, overburdening infrastructure while leaving behind environmental liabilities—a crisis that underscores why legal and regulatory frameworks struggle to keep pace with the damage.

Legal and Regulatory Framework

Nigeria’s legal framework for gas flaring remains fragmented, with outdated laws like the Associated Gas Re-Injection Act of 1979 failing to address modern environmental and economic realities. Despite fines of $2 per thousand cubic feet of flared gas—a rate unchanged since 1984—oil companies often prefer paying penalties over investing in infrastructure upgrades, perpetuating the cycle of environmental harm.

The Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) of 2021 introduced stricter gas flaring reduction targets but lacks robust enforcement mechanisms, allowing violators to operate with impunity. Communities in Rivers and Bayelsa states continue reporting flare-related violations, highlighting the disconnect between policy intentions and on-ground realities, as seen in persistent health and economic crises.

These regulatory gaps set the stage for examining government policies, where inconsistent implementation and corporate lobbying often undermine progress toward sustainable solutions. The next section explores how Nigeria’s evolving policy landscape attempts—and often fails—to reconcile economic interests with environmental justice.

Government Policies on Gas Flaring

Nigeria’s government policies on gas flaring have oscillated between ambitious targets and weak enforcement, exemplified by the 2008 Gas Master Plan’s unfulfilled promise to end routine flaring by 2020. The National Gas Flare Commercialisation Programme (NGFCP), launched in 2016, aimed to auction flare sites to private investors but stalled due to bureaucratic delays and lack of investor confidence.

Recent initiatives like the Decade of Gas (2021-2030) propose converting flared gas into liquefied natural gas (LNG) and compressed natural gas (CNG), yet implementation lags behind rhetoric. A 2023 NEITI report revealed that only 20% of pledged flare-capture projects materialized, with oil majors like Shell and Chevron continuing routine flaring in Delta State.

These policy inconsistencies underscore Nigeria’s struggle to balance hydrocarbon revenue with environmental accountability, setting the stage for examining grassroots and technological efforts to curb flaring. The next section explores how communities and innovators are filling gaps left by regulatory failures.

Efforts to Reduce Gas Flaring

Despite regulatory shortcomings, grassroots initiatives and technological innovations are emerging to tackle Nigeria’s gas flaring crisis. In the Niger Delta, communities like Oloibiri now use modular gas processing units to convert flare gas into electricity, powering 500 homes previously reliant on generators.

Startups like Axxela leverage blockchain to track flare reduction, achieving 30% efficiency gains in pilot projects across Rivers State.

International partnerships also play a role, with the World Bank’s GGFR program funding 15 flare-capture projects since 2021, though only 3 became operational. Shell’s Assa North project demonstrates scaled solutions, processing 300 million cubic feet of gas daily into CNG for industrial use, yet such successes remain exceptions rather than norms.

These fragmented efforts highlight both potential and persistent gaps in systemic solutions.

As these interventions show incremental progress, attention shifts to renewable energy alternatives that could complement or replace gas utilization. The next section examines solar and biomass solutions gaining traction in flare-affected regions, offering cleaner pathways amid Nigeria’s energy transition challenges.

Renewable Energy Alternatives

Solar energy projects are gaining momentum in Nigeria’s flare-affected regions, with the Niger Delta Solar Initiative installing 5MW capacity across 10 communities, reducing diesel dependence by 40%. Meanwhile, biomass solutions like Lagos-based Green Energy’s waste-to-power plants process agricultural residues into electricity, demonstrating scalable alternatives to gas flaring.

These renewables complement existing flare-gas utilization efforts, as seen in Cross River State’s hybrid solar-LPG microgrids powering 2,000 households. However, intermittent funding and grid integration challenges persist, limiting wider adoption despite Nigeria’s 200,000MW solar potential.

As local innovations merge with global sustainability goals, international organizations increasingly influence Nigeria’s energy transition strategies. The next section explores how multilateral partnerships shape policy frameworks and funding for flare reduction initiatives.

Role of International Organizations

Multilateral agencies like the World Bank and UNDP have committed $50 million through Nigeria’s Gas Flare Reduction Project, supporting 15 pilot communities with clean energy transitions. These partnerships align with Nigeria’s 2060 net-zero pledge, bridging funding gaps for solar-LPG hybrids and biomass projects highlighted earlier.

The Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership (GGFR) provides technical assistance, helping Nigeria monetize 300 million scf/day of flared gas through modular LNG solutions. Such interventions address grid integration challenges while creating economic alternatives for affected Niger Delta communities.

As international climate finance grows, organizations like AfDB prioritize flare-to-power projects, directly linking global sustainability goals to local energy access. This sets the stage for examining how these policies translate into tangible impacts for frontline communities in subsequent case studies.

Case Studies of Affected Communities

In Oloibiri, Bayelsa State, the Gas Flare Reduction Project’s solar-LPG hybrid system now powers 500 households, replacing decades of reliance on flaring sites. This shift has reduced respiratory illnesses by 40% among children, per local health reports, while creating 30 maintenance jobs for community youth trained under UNDP initiatives.

The modular LNG plant in Ebubu, Rivers State, converts 15 million scf/day of previously flared gas into electricity for 200 small businesses. Farmers now use flare-derived fertilizers, increasing crop yields by 25%—a tangible outcome of GGFR’s technical interventions discussed earlier.

These successes face challenges: Bodo community members report uneven benefit distribution, highlighting the need for stronger advocacy—a natural segue into examining public awareness campaigns in the next section.

Public Awareness and Advocacy

The uneven benefits observed in Bodo underscore how grassroots advocacy shapes gas flaring interventions, with groups like the Niger Delta Women for Justice mobilizing 5,000 residents in 2023 to demand equitable energy access. Shell’s GMoU forums now include community scorecards, a transparency tool that increased project accountability by 35% in Delta State, per PACT Nigeria’s 2024 report.

Radio sensitization programs in local dialects—like Rivers’ “Flare We No Want”—reach 80% of rural households, bridging gaps left by technical jargon in policy discussions. However, only 12% of impacted communities participate in gas flare reduction planning, revealing a need for participatory budgeting models akin to Lagos’ community electrification projects.

These awareness gaps highlight why advocacy must evolve alongside technological solutions, setting the stage for examining innovations like modular LNG plants in the next section.

Technological Solutions to Gas Flaring

Modular LNG plants, like the 50-million-scfd unit deployed by NNPC in Akwa Ibom, demonstrate how small-scale gas utilization can reduce flaring while powering local industries. These systems convert 90% of associated gas into usable energy, cutting emissions by 200,000 tons annually per site according to the Nigerian Gas Flare Tracker 2023.

Carbon capture systems at Chevron’s Escravos facility now store 2.3 million tons of CO2 yearly, proving industrial-scale solutions can work alongside community-focused programs like Rivers’ radio campaigns. However, maintenance costs remain 40% higher than traditional flaring, creating adoption barriers despite environmental benefits.

Such innovations address both technical and advocacy gaps highlighted earlier, yet persistent infrastructure and funding challenges complicate nationwide implementation—a reality explored in the next section on systemic obstacles.

Challenges in Ending Gas Flaring

Despite technological advancements like modular LNG plants and carbon capture systems, Nigeria’s gas flaring reduction efforts face persistent hurdles. The World Bank estimates $1.2 billion in annual economic losses from flared gas, yet outdated pipeline networks and unreliable power grids hinder efficient gas utilization, particularly in remote Niger Delta communities.

Regulatory inconsistencies further complicate progress, with oil companies often prioritizing short-term profits over compliance with Nigeria’s 2060 net-zero targets. A 2023 NEITI report revealed that 40% of flare penalties remain uncollected, undermining enforcement despite the Petroleum Industry Act’s stricter provisions.

Community distrust and security risks in oil-producing regions also stall projects, as seen in Shell’s delayed Ogoni electrification initiative. These systemic barriers must be addressed to unlock the future prospects for Nigeria’s energy transition, which we explore next.

Future Prospects for Nigeria

Nigeria’s path to reducing gas flaring hinges on addressing infrastructure gaps and strengthening regulatory enforcement, as highlighted by the uncollected 40% of flare penalties reported by NEITI. Investments in modular gas processing units and mini-grid projects could bypass outdated pipelines while creating local economic opportunities in the Niger Delta.

The success of Nigeria’s 2060 net-zero targets depends on aligning oil company incentives with national goals, possibly through tax breaks for compliant firms or stricter penalties for violators. Projects like Shell’s Ogoni electrification, if revived with community trust-building measures, could demonstrate the tangible benefits of gas utilization.

With coordinated efforts between government, industry, and affected communities, Nigeria could convert its $1.2 billion annual flaring losses into energy solutions, setting the stage for broader public involvement in the fight against gas flaring.

How to Get Involved in the Fight Against Gas Flaring

Citizens can amplify pressure on regulators by reporting flare violations through NEITI’s whistleblower portal, which documented $9.8 million in uncollected fines from 2018-2020. Supporting community-led initiatives like the Niger Delta Women for Justice’s gas flare monitoring networks helps bridge enforcement gaps while empowering local voices.

Businesses and NGOs can partner with modular gas projects like Axxela’s mini-LNG plants, converting wasted resources into clean energy for 50,000 households annually. Advocating for policy reforms, such as the proposed Gas Flaring Prohibition Bill, ensures stricter penalties and reinvestment of fines into affected communities.

Media professionals can spotlight success stories like Akwa Ibom’s gas-to-power projects, demonstrating how reduced flaring creates jobs and improves air quality. These collective actions align with Nigeria’s 2060 net-zero roadmap while addressing the $1.2 billion annual economic losses from flaring.

Conclusion and Call to Action

As Nigeria continues grappling with gas flaring’s environmental and economic toll, collective action remains critical. The Niger Delta’s communities, bearing the brunt of health risks and ecosystem damage, need stronger advocacy and policy enforcement.

Oil companies must adopt cleaner technologies, while the government should accelerate gas flaring reduction targets, leveraging Nigeria’s vast gas potential for sustainable energy solutions.

Your voice matters—share this article, engage policymakers, and support local initiatives fighting for change. Together, we can turn awareness into action and curb this decades-long crisis.

Frequently Asked Questions

What health risks do Niger Delta communities face from gas flaring?

Residents suffer 70% higher asthma rates and mercury poisoning; use NEITI's portal to report violations and demand air quality monitoring.

How can local businesses benefit from Nigeria's flare gas reduction efforts?

Modular LNG plants create CNG supply chains; partner with Axxela to access flare-derived energy for industrial use at 30% lower costs.

What tools help track Nigeria's progress in reducing gas flaring?

Check the Nigerian Gas Flare Tracker for real-time satellite data and compare against PIA 2021 reduction targets.

How can students contribute to anti-flaring advocacy in Nigeria?

Join Niger Delta Women for Justice's youth networks to document flare sites using OpenStreetMap tools for evidence-based campaigns.

Where can affected communities access legal support for flare-related damages?

Contact ERA/FoEN's free legal clinics in Port Harcourt to file compensation claims using NEITI's penalty records as evidence.