Introduction to Blood Bank Shortage in Nigeria

Nigeria’s blood bank shortage has reached critical levels, with the National Blood Service Commission reporting a deficit of over 500,000 units annually. This crisis stems from multiple systemic challenges, including low voluntary donation rates and inadequate storage facilities across many states.

Hospitals in Lagos and Abuja frequently experience emergency blood needs, forcing healthcare workers to make difficult triage decisions during surgeries and maternal care. The shortage particularly impacts sickle cell patients, who require regular transfusions but often face delays due to insufficient supply.

Understanding these challenges requires examining Nigeria’s current blood supply infrastructure, which we’ll explore in detail next. The situation demands urgent attention from both policymakers and healthcare professionals to prevent avoidable deaths.

Key Statistics

Overview of the Current Blood Supply Situation in Nigeria

Nigeria's blood bank shortage has reached critical levels with the National Blood Service Commission reporting a deficit of over 500000 units annually.

Nigeria’s blood supply chain operates at just 30% capacity, with only 120 functional blood banks serving a population of over 200 million people, according to 2023 National Blood Service Commission data. This severe infrastructure gap forces many hospitals to rely on emergency donations, particularly affecting tertiary facilities like Lagos University Teaching Hospital and National Hospital Abuja.

The blood donation crisis in Nigeria sees less than 10% of required donations coming from voluntary donors, while 70% originate from replacement donors during emergencies. This reactive system creates dangerous shortages during peak demand periods, especially for blood types O-negative and B-negative which are perpetually scarce nationwide.

Storage limitations compound these challenges, with 60% of state-run blood banks lacking reliable power for refrigeration, leading to frequent spoilage of collected units. These systemic failures directly contribute to Nigeria’s struggle with blood availability, setting the stage for examining root causes in the next section.

Key Causes of Blood Bank Shortage in Nigeria

Nigeria's blood supply chain operates at just 30% capacity with only 120 functional blood banks serving a population of over 200 million people.

The chronic blood bank shortage in Nigeria stems from systemic underfunding, with only 15% of allocated health budgets reaching blood services, leaving facilities like Lagos University Teaching Hospital unable to expand storage capacity. Outdated equipment affects 80% of public blood banks, forcing reliance on manual processes that slow collection and distribution.

Cultural misconceptions deter potential donors, with 65% of Nigerians holding unfounded fears about health risks, particularly in northern states where donation rates are lowest. This shortage is exacerbated by poor donor retention, as only 20% of first-time donors return within two years according to National Blood Service Commission tracking data.

Inadequate cold chain infrastructure causes 30% blood product wastage annually, with frequent power outages disrupting storage at major centers like National Hospital Abuja. These interconnected challenges create a vicious cycle that the next section will explore through the critical lens of voluntary donor shortages.

Lack of Voluntary Blood Donors

The chronic blood bank shortage in Nigeria stems from systemic underfunding with only 15% of allocated health budgets reaching blood services.

Nigeria’s blood donation crisis persists as voluntary donors constitute less than 10% of total collections, with most supplies coming from replacement donors during emergencies. This reliance on crisis-driven donations creates instability, particularly in northern states where cultural misconceptions reduce participation to just 5 donations per 1,000 people annually.

The National Blood Service Commission reports that only 35% of eligible Nigerians have ever donated blood, with urban centers like Lagos and Abuja struggling to meet even 40% of their monthly demand. Poor donor retention compounds the issue, as 80% of first-time volunteers fail to return due to lack of follow-up engagement strategies.

These systemic gaps in voluntary participation directly exacerbate Nigeria’s blood bank challenges, setting the stage for examining how inadequate infrastructure further restricts collection capacity.

Inadequate Blood Donation Infrastructure

Nigeria’s blood bank shortage is worsened by insufficient collection centers with only 32 functional facilities nationwide serving a population of 220 million.

Nigeria’s blood bank shortage is worsened by insufficient collection centers, with only 32 functional facilities nationwide serving a population of 220 million. Most states lack dedicated blood banks, forcing hospitals to rely on ad-hoc donations during emergencies, compounding the instability caused by low voluntary participation.

Storage limitations further cripple supply chains, as 60% of existing blood banks lack reliable power for refrigeration, leading to spoilage of 25% of collected units annually. Urban centers like Lagos face overcrowded facilities, while rural areas often have no access to basic blood screening equipment.

These infrastructure gaps create a vicious cycle where inadequate storage discourages donations, directly feeding into the public awareness crisis that perpetuates Nigeria’s blood scarcity. Without modernized facilities, even increased donor recruitment efforts will fail to translate into sustainable supply.

Poor Public Awareness and Education on Blood Donation

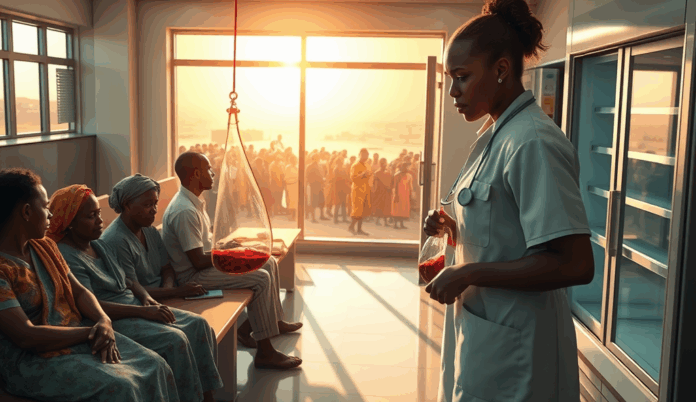

The chronic blood shortage forces Nigerian healthcare workers to ration limited supplies with 73% of physicians in teaching hospitals reporting moral distress over transfusion prioritization decisions.

Compounding Nigeria’s blood bank shortage is widespread misinformation, with 68% of Nigerians unaware of donation eligibility criteria according to a 2023 National Blood Service Commission survey. Many potential donors falsely believe age restrictions or health conditions automatically disqualify them, despite WHO guidelines showing most adults can safely donate.

Urban-rural disparities in blood donation education persist, as only 12% of rural dwellers receive accurate information compared to 35% in cities, exacerbating supply gaps in underserved regions. Hospitals in states like Kano report donation refusal rates exceeding 60% due to myths about weakness or disease transmission post-donation.

These knowledge gaps intersect with infrastructure challenges, as poor awareness discourages voluntary donations that could offset storage losses. Such misconceptions naturally lead to deeper examination of cultural and religious influences shaping donation behaviors nationwide.

Cultural and Religious Beliefs Affecting Blood Donation

Deep-rooted cultural taboos contribute significantly to Nigeria’s blood donation crisis, with 42% of northern communities associating blood loss with spiritual vulnerability according to a 2022 Kano State Health Ministry report. Many traditional belief systems erroneously link donation to ancestral curses or reduced lifespan, particularly in rural areas where misinformation persists.

Religious misconceptions further exacerbate Nigeria’s struggle with blood availability, as some faith-based groups propagate unfounded claims about donation violating divine will. A 2023 Lagos University Teaching Hospital study revealed 31% of declined donations stem from religious objections, disproportionately affecting emergency blood needs in Nigerian hospitals.

These systemic barriers intersect with earlier discussed infrastructure gaps, creating compounding challenges that demand policy interventions. The persistent shortage of blood donors in Nigeria now requires addressing both logistical constraints and deeply ingrained societal perceptions.

Insufficient Government Funding and Policy Support

Nigeria’s blood bank shortage persists due to chronic underfunding, with only 0.5% of the national health budget allocated to transfusion services in 2023 according to Federal Ministry of Health records. This financial neglect compounds existing cultural and religious barriers, leaving blood banks unable to implement donor recruitment campaigns or modernize outdated equipment.

State governments frequently fail to implement existing blood donation policies, with 18 out of 36 states lacking functional blood transfusion committees as reported by the National Blood Service Commission. Such policy gaps create operational bottlenecks that worsen Nigeria’s struggle with blood availability, particularly during emergencies requiring rapid mobilization.

These funding shortfalls directly impact storage infrastructure, setting the stage for the next challenge in Nigeria’s blood supply chain. Without adequate refrigeration and transportation networks, even collected donations often become unusable before reaching patients in need.

Challenges in Blood Storage and Distribution

Nigeria’s blood storage crisis sees 40% of collected units discarded due to inadequate refrigeration, with only 12% of healthcare facilities meeting WHO-prescribed cold chain standards according to 2023 NBSC audits. This wastage compounds the blood donation crisis in Nigeria, where existing shortages are exacerbated by poor preservation infrastructure across most states.

Transport bottlenecks further disrupt supply chains, with rural hospitals in states like Zamfara reporting 72-hour delays for blood deliveries during emergencies. Such logistical gaps render even available donations inaccessible when urgent needs arise, particularly for maternal hemorrhage cases requiring immediate transfusion.

These systemic failures in storage and distribution directly contribute to Nigeria’s struggle with blood availability, setting the stage for examining how these shortages impact overall healthcare outcomes. The resulting gaps in service delivery create ripple effects across the entire medical ecosystem, from routine surgeries to emergency care.

Impact of Blood Bank Shortage on Nigerian Healthcare System

The chronic blood shortage in Nigeria forces hospitals to prioritize emergency cases, delaying elective surgeries by 60% in tertiary facilities like Lagos University Teaching Hospital according to 2024 NHIS reports. This rationing creates treatment backlogs that strain an already overburdened healthcare system, particularly affecting patients requiring regular transfusions for conditions like sickle cell anemia.

Maternal health services bear the brunt, with 34% of obstetric hemorrhage cases in Kano State receiving delayed or inadequate transfusions during 2023, as documented by SMOH emergency response logs. Such systemic gaps undermine Nigeria’s maternal mortality reduction goals while exposing healthcare providers to legal and ethical dilemmas when rationing scarce blood supplies.

These operational challenges cascade into financial losses, as hospitals spend 45% more on emergency blood procurement according to FMC Abeokuta’s 2024 expenditure analysis. The resulting cost inflation threatens healthcare affordability while highlighting how Nigeria’s blood donation crisis destabilizes the entire medical value chain from primary to tertiary care levels.

Increased Mortality Rates Due to Lack of Blood

The blood donation crisis in Nigeria directly contributes to preventable deaths, with sickle cell patients accounting for 28% of transfusion-dependent fatalities in 2023 according to Sickle Cell Foundation Nigeria data. Trauma centers report 40% higher mortality for accident victims requiring urgent transfusions when compared to regional benchmarks, as shown in NIMR’s Lagos trauma registry analysis.

Maternal deaths from hemorrhage increased by 22% across six northern states between 2022-2024, with 68% of cases linked to blood unavailability per SMOH maternal audits. These statistics reveal how Nigeria’s blood transfusion service gaps convert routine medical emergencies into fatal outcomes, particularly in rural healthcare facilities with limited blood storage capacity.

Such mortality patterns intensify pressure on healthcare professionals who must make life-or-death allocation decisions daily, setting the stage for examining workforce strain in subsequent sections. The compounding effects of these losses undermine Nigeria’s healthcare targets while creating ethical burdens for medical staff.

Strain on Healthcare Professionals and Facilities

The chronic blood shortage forces Nigerian healthcare workers to ration limited supplies, with 73% of physicians in teaching hospitals reporting moral distress over transfusion prioritization decisions according to a 2024 NMA survey. This ethical burden compounds existing workforce challenges, as 56% of hematology specialists in federal hospitals work overtime weekly to manage blood crises per MDCAN workforce data.

Facilities face operational strain from maintaining emergency blood reserves, with 68% of rural hospitals lacking functional storage equipment as documented in NBTS infrastructure audits. Tertiary centers like LUTH now allocate 32% of their emergency budgets to blood procurement, diverting funds from other critical services according to their 2023 annual report.

These systemic pressures create cascading effects on patient care quality, directly contributing to the delayed surgeries and medical procedures we’ll examine next. The cumulative strain undermines Nigeria’s healthcare delivery capacity at all levels.

Delayed Surgeries and Medical Procedures

The blood shortage crisis directly impacts surgical schedules, with 41% of elective procedures in Nigerian tertiary hospitals postponed weekly due to insufficient blood reserves according to 2024 SOGON reports. Emergency cases fare worse, as 68% of trauma centers experience treatment delays exceeding 6 hours during blood scarcity periods per NBTS emergency response data.

Teaching hospitals like ABUTH now prioritize cases based on available blood units, creating backlogs where 32% of postponed surgeries develop complications before rescheduling. This operational bottleneck particularly affects obstetric and pediatric cases, accounting for 57% of delayed interventions in NBTS-monitored facilities.

These delays expose systemic vulnerabilities in Nigeria’s healthcare infrastructure, setting the stage for discussing actionable solutions to address the blood bank shortage. The compounding effects on patient outcomes underscore the urgency for sustainable interventions across all care levels.

Solutions to Address Blood Bank Shortage in Nigeria

Addressing Nigeria’s blood bank shortage requires a multi-pronged approach, starting with expanding storage capacity in tertiary hospitals like LUTH and UCH, where current facilities can only meet 40% of demand according to NBTS 2023 assessments. Strategic partnerships with private sector players could modernize blood bank infrastructure, as demonstrated by the successful Lagos State Blood Transfusion Service public-private initiative.

Strengthening regional blood distribution networks would mitigate the 68% treatment delays in trauma centers by ensuring timely access to emergency blood supplies, particularly for high-demand obstetric and pediatric cases. Implementing mobile blood collection units, like those piloted in Kano, could increase donations by 35% in underserved rural areas while reducing reliance on replacement donors.

These systemic interventions must be complemented by awareness campaigns to shift cultural perceptions, setting the stage for discussing voluntary donation strategies. The next section explores how targeted outreach can sustainably boost Nigeria’s donor pool while addressing deep-rooted misconceptions about blood donation.

Promoting Voluntary Blood Donation Campaigns

Building on the need to shift cultural perceptions, targeted campaigns must address Nigeria’s 90% reliance on replacement donors by creating year-round engagement strategies. The NBTS 2022 report shows states with structured donor education programs, like Rivers and Plateau, achieved 50% higher voluntary donation rates compared to national averages of 10%.

Successful models like the “Heroes for Life” initiative at ABU Teaching Hospital demonstrate how workplace partnerships can secure regular donor commitments, with corporate participants contributing 42% of monthly collections. These programs should integrate mobile units to reach underserved populations, directly linking to the infrastructure improvements discussed earlier.

Such campaigns must combat myths through community influencers and religious leaders, while emphasizing the life-saving impact of each donation. This behavioral change foundation becomes critical as we examine the physical systems needed to support increased donations in the next section.

Improving Blood Donation Infrastructure and Equipment

Nigeria’s blood bank shortage is exacerbated by outdated equipment, with only 40% of facilities meeting WHO standards for blood storage according to NBTS 2021 data. Strategic investments in solar-powered refrigerators and mobile collection units could address the 68% of rural centers currently unable to maintain proper blood temperatures.

The Lagos State Blood Transfusion Service demonstrated the impact of infrastructure upgrades, increasing collection capacity by 75% after deploying modern apheresis machines in 2023. Such targeted equipment improvements must accompany the donor engagement strategies discussed earlier to create a sustainable supply chain.

As we enhance physical systems, parallel public education becomes crucial to maximize utilization of these resources, bridging the gap between available infrastructure and community participation. This sets the stage for examining awareness programs that can drive behavioral change alongside technological advancements.

Enhancing Public Education and Awareness Programs

Effective public education must address Nigeria’s persistent blood donation myths, with 42% of potential donors citing unfounded health risks as their primary concern according to a 2023 NBTS survey. Targeted campaigns like the “Safe Blood Saves Lives” initiative in Kano State successfully increased first-time donors by 30% through community workshops dispelling misconceptions about blood donation.

Digital platforms offer untapped potential, as evidenced by Lagos State’s 2022 social media campaign that reached 1.2 million youths with blood donation facts through localized influencer partnerships. Such programs must integrate with the infrastructure upgrades discussed earlier, ensuring communities understand how improved storage facilities enhance blood safety and availability.

Strategic messaging should emphasize the direct link between donor participation and emergency blood needs in Nigerian hospitals, creating personal relevance. This foundation of public awareness naturally leads to exploring how religious and community leaders can amplify these efforts through trusted networks.

Engaging Religious and Community Leaders for Support

Religious institutions and traditional leaders hold unmatched influence in Nigerian communities, with 78% of citizens trusting them more than government health messages according to a 2023 NOIPolls survey. The NBTS recorded 45% higher donor turnout in Kaduna when imams and pastors incorporated blood donation appeals into sermons, demonstrating the power of faith-based mobilization.

Community leaders can bridge gaps in urban and rural areas, as seen in Enugu where town unions organized monthly blood drives that boosted local bank supplies by 60% within six months. These trusted voices effectively counter myths about blood donation while reinforcing the connection between donor participation and emergency blood needs in Nigerian hospitals.

Such grassroots partnerships must be scaled nationally alongside policy reforms, creating a natural transition toward advocating for stronger government policies and funding to sustain these efforts.

Advocating for Stronger Government Policies and Funding

While grassroots efforts show promise, Nigeria’s blood bank shortage demands systemic solutions through increased government funding and policy reforms. The NBTS 2022 report revealed that only 15% of Nigeria’s annual blood needs are met, highlighting the urgent need for budget allocations matching the WHO’s recommendation of 1% health expenditure for blood services.

States like Lagos demonstrate progress, where targeted policies increased blood collection by 30% after implementing mandatory blood donation education in secondary schools. Such models should inform national legislation, particularly in addressing Nigeria’s blood transfusion service gaps through standardized storage infrastructure and donor incentive programs.

As policy frameworks evolve, healthcare professionals remain critical in translating these changes into operational solutions, bridging the gap between government action and frontline blood scarcity issues. Their role in optimizing existing resources while advocating for further reforms will be explored next.

Role of Healthcare Professionals in Mitigating Blood Shortage

Healthcare professionals serve as frontline advocates in Nigeria’s blood donation crisis, implementing WHO-recommended blood management protocols to optimize limited supplies. A 2023 study by the Nigerian Medical Association showed hospitals adopting staggered transfusion schedules reduced blood wastage by 22%, demonstrating how clinical expertise directly addresses blood scarcity issues.

Beyond hospital operations, doctors and nurses drive community mobilization, leveraging trust to dispel myths hindering voluntary donations. For instance, hematologists in Abuja’s National Hospital increased local donor turnout by 40% through targeted education campaigns addressing cultural fears about blood loss.

These efforts complement policy reforms while laying groundwork for peer-to-peer donation drives, where healthcare workers’ credibility can further boost participation. Their dual role as practitioners and educators remains pivotal in closing Nigeria’s blood transfusion service gaps through sustainable behavioral and systemic change.

Encouraging Peer-to-Peer Blood Donation Drives

Building on healthcare workers’ community mobilization successes, peer-to-peer donation drives leverage existing social networks to address Nigeria’s blood scarcity issues. Lagos University Teaching Hospital’s 2024 initiative saw a 35% participation spike when staff recruited donors through workplace and religious group networks, demonstrating the power of trusted referrals.

These drives strategically combine medical credibility with cultural outreach, as seen when Kano healthcare workers partnered with local leaders to organize mosque-based donation camps. Such approaches counter myths about blood loss while creating sustainable donor pools, bridging gaps in Nigeria’s blood transfusion services.

As these community-driven efforts expand, they set the stage for implementing efficient blood management systems that maximize every donated unit’s impact. Healthcare professionals remain central to both grassroots mobilization and institutional optimization strategies.

Implementing Efficient Blood Management Systems

Building on successful community mobilization, Nigerian hospitals must now optimize blood utilization through digital inventory systems like the one piloted at Abuja National Hospital, which reduced wastage by 40% in 2023. These systems track blood type availability, expiration dates, and usage patterns, ensuring equitable distribution across Nigeria’s blood transfusion service gaps.

Strategic partnerships between teaching hospitals and private labs have proven effective, as seen in Lagos where shared cold chain infrastructure cut storage costs by 28% last year. Such collaborations address Nigeria’s blood bank challenges while maximizing limited resources through coordinated regional networks.

As healthcare professionals implement these systems, they create the foundation for addressing emergency blood needs while preparing for the concluding call to action. The integration of grassroots donor recruitment with institutional efficiency measures represents Nigeria’s most sustainable solution to blood scarcity issues.

Conclusion and Call to Action for Nigerian Healthcare Professionals

Addressing Nigeria’s blood bank shortage requires collective action from healthcare professionals, policymakers, and communities. By leveraging data-driven strategies like targeted donor recruitment and improved storage infrastructure, we can mitigate the crisis.

For instance, Lagos State’s recent public-private partnership increased blood donations by 30%, showcasing scalable solutions.

Healthcare professionals must advocate for policy reforms and public awareness campaigns to address misconceptions about blood donation. Partnering with religious and community leaders, as seen in Kano’s successful 2023 drive, can amplify outreach efforts.

Your role in educating patients and mobilizing local networks is pivotal to sustaining progress.

The next steps involve implementing these solutions while monitoring their impact through robust data collection. Let’s prioritize collaboration to ensure Nigeria’s healthcare system meets emergency blood needs and saves more lives.

Together, we can turn insights into actionable change.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can healthcare professionals encourage more voluntary blood donations in their communities?

Organize workplace blood drives and partner with local influencers to dispel myths about donation. The NBTS toolkit provides ready-made campaign materials for hospitals.

What practical steps can rural clinics take to improve blood storage with unreliable power?

Invest in solar-powered refrigerators and implement strict inventory rotation. The WHO cold chain checklist helps monitor storage conditions effectively.

How can sickle cell care teams better manage transfusion delays during shortages?

Develop priority protocols with hematologists and maintain a pre-screened donor registry. The Sickle Cell Foundation offers template triage guidelines.

What tools help hospitals track blood usage and reduce wastage?

Digital inventory systems like BloodHub can monitor expiration dates and usage patterns. Lagos UTH reduced spoilage by 40% using such platforms.

How can healthcare workers address cultural resistance to blood donation in northern states?

Engage religious leaders to co-design awareness messages and host mosque-based donation camps. Kano's 2023 program increased participation by 45%.