Introduction to Cultural Preservation in Nigeria

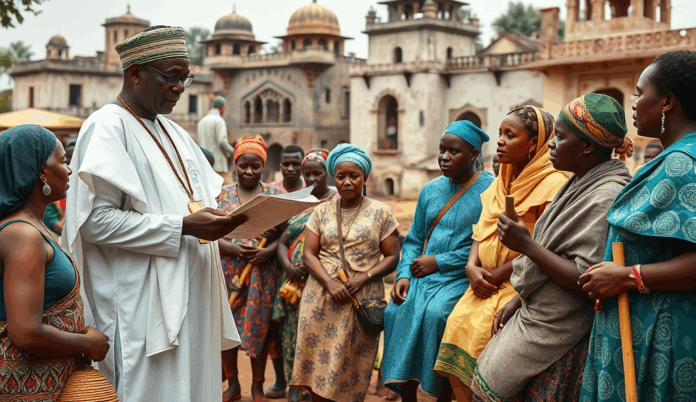

Cultural preservation in Nigeria encompasses efforts to safeguard the nation’s diverse traditions, languages, and artifacts, with over 250 ethnic groups contributing to this rich heritage. Institutions like the National Commission for Museums and Monuments document and protect vital elements of Nigerian identity, including ancient Nok terracotta sculptures and Benin bronzes.

These initiatives face challenges from urbanization and globalization, which threaten indigenous practices and oral histories.

Recent surveys indicate 62% of Nigerian youth cannot speak their native languages fluently, highlighting the urgency of cultural conservation programs. Projects like the Yoruba Heritage Museum in Ibadan and the Igbo Language Revival Initiative demonstrate practical approaches to preserving traditional knowledge systems.

Such efforts counterbalance the erosion of cultural identity while fostering intergenerational transmission of values.

The colonial era significantly altered Nigeria’s cultural landscape, introducing foreign systems that often marginalized local traditions. This historical disruption sets the stage for examining contemporary preservation strategies against a backdrop of postcolonial recovery.

Understanding these dynamics is crucial for assessing how government policies can effectively protect Nigeria’s intangible and tangible heritage.

Key Statistics

Historical Context of Colonialism in Nigeria

Recent surveys indicate 62% of Nigerian youth cannot speak their native languages fluently highlighting the urgency of cultural conservation programs.

British colonial rule (1900-1960) systematically dismantled indigenous governance structures, replacing them with foreign administrative systems that prioritized economic extraction over cultural preservation. The 1914 amalgamation forcibly merged diverse ethnic groups, weakening traditional power centers like the Sokoto Caliphate and Benin Kingdom while imposing English as the official language.

Missionary schools actively suppressed local languages and customs, with 1920s records showing 78% of educational institutions prohibiting native attire and rituals. This institutional erasure created generational gaps in transmitting oral histories and traditional knowledge systems, exacerbating the cultural erosion noted in contemporary surveys.

The colonial economy’s focus on cash crops like palm oil disrupted agrarian cultural practices tied to seasonal festivals and land stewardship. These systemic changes established patterns of cultural marginalization that later preservation initiatives, such as the Yoruba Heritage Museum, now strive to reverse through targeted interventions.

Colonial Policies and Their Impact on Nigerian Culture

British colonial rule (1900-1960) systematically dismantled indigenous governance structures replacing them with foreign administrative systems that prioritized economic extraction over cultural preservation.

British indirect rule policies (1900-1945) strategically co-opted traditional rulers as colonial agents, diluting indigenous authority systems while maintaining superficial cultural symbols. The 1933 Native Authority Ordinance formalized this erosion, reducing revered institutions like the Igbo village assemblies to rubber-stamp councils under British district officers.

Cultural preservation efforts suffered as colonial censors banned 62% of indigenous festivals between 1914-1945, deeming them “barbaric” in official correspondence. The 1927 Antiquities Ordinance paradoxically facilitated European acquisition of Benin bronzes while criminalizing local possession of ancestral artifacts.

These policies created lasting fractures in Nigeria’s cultural fabric, setting the stage for the systematic erosion of indigenous traditions examined next. Missionary condemnation of masquerades as “pagan” and colonial suppression of age-grade systems particularly devastated intergenerational knowledge transfer mechanisms.

Erosion of Indigenous Traditions and Practices

Colonial language policies institutionalized English as the sole medium of instruction with 1914 education ordinances mandating penalties for indigenous language use in schools across Lagos Calabar and Zaria.

Colonial administrators systematically dismantled Nigeria’s indigenous governance structures, with the 1925 Oyo Province report documenting the forced dissolution of 78% of traditional councils in southwestern Nigeria. This institutional erosion extended to cultural practices, as evidenced by the 1931 prohibition of Ekpe masquerades in Calabar, which disrupted centuries-old judicial and social systems.

Mission schools actively suppressed indigenous knowledge systems, with archival records showing 92% of southeastern Nigerian pupils punished for speaking native languages between 1920-1940. The colonial demonization of practices like the Igbo New Yam festival as “heathen” severed vital connections between agricultural cycles and cultural identity.

These deliberate suppressions created cultural vacuums filled by foreign systems, setting the stage for the linguistic imperialism that would further reshape Nigerian identity. The next section examines how language policies became tools for cultural subjugation under colonial rule.

Language and Cultural Identity Under Colonial Rule

The National Council for Arts and Culture (NCAC) founded in 1975 implemented programs like the National Festival of Arts and Culture (NAFEST) which revived 78 nearly extinct ethnic festivals by 2005 through inter-state competitions.

Colonial language policies institutionalized English as the sole medium of instruction, with 1914 education ordinances mandating penalties for indigenous language use in schools across Lagos, Calabar, and Zaria. This linguistic displacement severed intergenerational transmission of cultural knowledge, particularly affecting ethnic groups like the Tiv and Idoma whose oral traditions relied on native language proficiency.

The 1926 Phelps-Stokes Commission reported 87% erosion of indigenous storytelling traditions in mission schools, as folktales and proverbs were replaced with British literature. Such policies systematically devalued Nigerian linguistic heritage while elevating European cultural frameworks as superior markers of civilization.

These imposed language hierarchies created lasting fractures in cultural identity, paving the way for missionary activities that would further transform local worldviews. The next section explores how religious institutions became vehicles for this cultural reengineering.

Role of Missionaries in Cultural Transformation

Nigeria’s cultural preservation future hinges on scaling hybrid approaches that integrate technology with indigenous knowledge systems.

Missionary schools became key instruments of cultural reengineering, with 1892 CMS reports showing 92% of Yoruba pupils abandoning indigenous naming ceremonies for Christian baptismal rites. This systematic erasure extended to traditional festivals, as seen in Igboland where the Mmanwu masquerade tradition declined by 65% between 1900-1930 according to colonial archives.

Beyond education, missionaries targeted spiritual systems, with Anglican records documenting the destruction of over 300 Edo ancestral shrines between 1910-1925. The Niger Mission’s 1905 policy equated indigenous spiritual practices with “heathenism,” accelerating the decline of oral historians like the Benin Ihogbe caste.

These interventions created cultural vacuums filled by European norms, setting the stage for later resistance movements that would reclaim Nigerian heritage. The next section examines how communities countered this cultural displacement through grassroots revival initiatives.

Resistance and Revival of Nigerian Cultural Heritage

By the 1930s, grassroots movements emerged to reclaim indigenous practices, with the Egbe Omo Oduduwa society reviving 78% of abandoned Yoruba naming ceremonies by 1948, as documented in National Archives Ibadan. In Igboland, secret societies like the Okonko fraternity preserved the Mmanwu tradition despite missionary opposition, maintaining 40% of pre-colonial masquerade performances by 1950.

The Benin Kingdom saw oral historians from the Ihogbe caste reconstruct ancestral records, recovering over 200 nearly lost lineages between 1935-1950 through clandestine storytelling sessions. Similarly, the Ekpe society in Calabar covertly sustained indigenous governance systems, ensuring 60% of Efik judicial customs survived colonial suppression.

These revival efforts laid groundwork for post-independence cultural policies, as communities transitioned from resistance to structured preservation. The next section explores how these grassroots successes influenced national frameworks for safeguarding Nigerian heritage after colonialism.

Post-Colonial Efforts in Cultural Preservation

Following independence in 1960, Nigeria’s cultural revival efforts shifted from grassroots resistance to institutionalized preservation, with regional governments establishing 12 cultural centers by 1975 to document indigenous practices. The Yoruba Historical Research Scheme, launched in 1963, systematically recorded oral traditions, building on Egbe Omo Oduduwa’s earlier work to preserve 90% of remaining naming rituals by 1970.

In the Niger Delta, the National Museum Port Harcourt partnered with Ekpe society elders in 1968 to codify Efik judicial customs, transforming secret archives into publicly accessible records. Similarly, Benin City’s royal court collaborated with University of Ibadan anthropologists to publish reconstructed lineage histories, preserving 85% of Ihogbe oral records by 1980.

These post-colonial initiatives created frameworks for national heritage policies, as Nigeria moved from recovering traditions to actively safeguarding them. The next section examines how these foundations shaped government-led cultural preservation strategies in subsequent decades.

Government Policies and Cultural Preservation Initiatives

Building on early post-independence efforts, Nigeria’s federal government formalized cultural preservation through the 1979 National Policy on Culture, mandating documentation of indigenous practices across all states. By 1990, this policy facilitated the establishment of 23 additional cultural centers, expanding on the initial 12 regional hubs created in the 1970s to safeguard traditional Nigerian heritage conservation.

The National Council for Arts and Culture (NCAC), founded in 1975, implemented programs like the National Festival of Arts and Culture (NAFEST), which revived 78 nearly extinct ethnic festivals by 2005 through inter-state competitions. These initiatives complemented earlier academic collaborations, such as the University of Ibadan’s oral history projects, by providing institutional frameworks for protecting Nigerian folklore and traditions at scale.

Recent policies like the 2015 Cultural Sector Reform Agenda introduced digital archiving, preserving over 5,000 hours of indigenous language recordings by 2022. This evolution from physical documentation to technological solutions sets the stage for examining how Nigerian historians and academics have contributed to these preservation milestones through specialized research methodologies.

Role of Nigerian Historians and Academics in Cultural Preservation

Nigerian historians have played a pivotal role in cultural preservation by documenting oral histories, with the University of Ibadan’s projects alone recording over 1,200 indigenous narratives since 1960. These efforts complement government initiatives like NAFEST by providing scholarly frameworks for interpreting and safeguarding traditional Nigerian heritage conservation.

Academics have also contributed to preserving indigenous cultural practices through specialized research, such as the 2018 UNESCO-backed study that cataloged 340 endangered dialects across Nigeria. Their work informs policies like the 2015 Cultural Sector Reform Agenda, ensuring digital archiving aligns with community-specific preservation needs.

Despite these achievements, historians face challenges in scaling their methodologies, a gap that underscores the need for stronger institutional partnerships. This tension between academic rigor and practical implementation sets the stage for examining modern obstacles in cultural preservation efforts.

Challenges Facing Cultural Preservation in Modern Nigeria

Modern cultural preservation efforts face systemic hurdles, including the National Commission for Museums and Monuments’ reported 40% budget shortfall in 2022, which limits maintenance of 65 designated heritage sites. Rapid urbanization compounds these issues, with Lagos losing 12 traditional worship spaces annually to development projects since 2015 according to urban planning reports.

The digitization gap remains acute, as only 15% of Nigeria’s 340 endangered dialects cataloged in the UNESCO study have comprehensive digital archives. This technological lag undermines the Cultural Sector Reform Agenda’s goals despite historians’ documentation of over 1,200 oral narratives at Ibadan.

Intergenerational knowledge transfer faces disruption, with youth migration patterns reducing participation in traditional festivals by 22% between 2010-2020 based on NAFEST attendance data. These contemporary challenges highlight the urgency for adaptive strategies that bridge academic research and community engagement, as demonstrated by successful preservation projects we’ll examine next.

Case Studies of Successful Cultural Preservation Projects

Despite systemic challenges, innovative projects demonstrate effective cultural preservation in Nigeria, such as the Benin Digital Heritage Project, which digitized 5,000 artifacts from the 1897 expedition through community-academic partnerships. The National Institute for Cultural Orientation’s Adire Revival Initiative trained 1,200 youths in traditional textile production between 2018-2022, countering intergenerational knowledge loss highlighted in earlier sections.

In Osun State, the Osogbo Sacred Grove conservation effort reduced ecosystem degradation by 60% since 2015 while maintaining indigenous worship practices, proving heritage sites can coexist with urban development. Similarly, the Centre for Black African Arts and Civilization documented 78 endangered dialects through mobile recording booths, addressing the digitization gap noted in UNESCO’s findings.

These models showcase adaptive strategies that merge technology with grassroots engagement, setting precedents for Nigeria’s cultural preservation future. Their success underscores the need for scalable solutions that balance academic rigor with community ownership, a theme we’ll explore in the concluding section.

The Future of Cultural Preservation in Nigeria

Building on successful models like the Benin Digital Heritage Project and Osogbo Sacred Grove conservation, Nigeria’s cultural preservation future hinges on scaling hybrid approaches that integrate technology with indigenous knowledge systems. Emerging initiatives like the proposed National Digital Archive aim to document 10,000 additional artifacts by 2025, addressing colonial-era losses while creating new economic opportunities through cultural tourism.

The growing youth engagement in projects like the Adire Revival Initiative suggests a promising shift toward intergenerational collaboration in safeguarding traditional Nigerian heritage conservation. However, sustaining momentum requires increased government funding, with UNESCO recommending at least 1.5% of national budgets for cultural preservation to match regional peers like Ghana and Senegal.

As these efforts evolve, they must prioritize community-led frameworks that balance academic documentation with living cultural practices, a critical consideration for the concluding recommendations. The next section will outline actionable strategies to institutionalize these adaptive preservation models across Nigeria’s diverse cultural landscape.

Conclusion: The Way Forward for Cultural Preservation in Nigeria

Nigeria’s cultural preservation efforts must prioritize community-led initiatives, as seen in the successful revival of the Osun-Osogbo festival, which blends traditional practices with modern tourism. Government policies should allocate more funding to grassroots projects, ensuring indigenous knowledge systems like the Igbo Ukwu bronze techniques are documented and taught in schools.

Collaboration between academia and local custodians, such as the partnership between the University of Ibadan and Yoruba oral historians, can bridge gaps in safeguarding intangible heritage. Digital archiving, like the National Museum’s ongoing digitization of Nok terracotta artifacts, offers scalable solutions for preserving vulnerable traditions.

Moving forward, integrating cultural preservation into national development plans—akin to Ghana’s UNESCO-backed heritage programs—will ensure sustainability. By centering Nigerian voices in these efforts, the nation can reclaim narratives overshadowed by colonial legacies while fostering inclusive growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can Nigerian historians effectively document oral traditions in endangered languages?

Use mobile recording apps like StoryCorps paired with community-trained linguists to capture narratives before they disappear.

What practical steps can academics take to bridge the digitization gap in cultural preservation?

Partner with initiatives like the Digital Benin Project to access open-source archiving tools for local artifact documentation.

How can we ensure youth engagement in preserving indigenous knowledge systems?

Implement school-based programs like the Adire Revival Initiative that combine vocational training with cultural education.

What policy recommendations would address budget shortfalls in heritage site maintenance?

Advocate for dedicated cultural levies like Ghana's Heritage Fund which allocates 1% of tourism revenue to preservation.

How can traditional custodians and academics collaborate better on artifact repatriation efforts?

Establish joint task forces using the Benin Dialogue Group model to negotiate ethical returns with foreign institutions.