Here is the JSON array of the content outline for “Fiscal Federalism in Nigeria” tailored to the targeted audience on a WordPress platform:

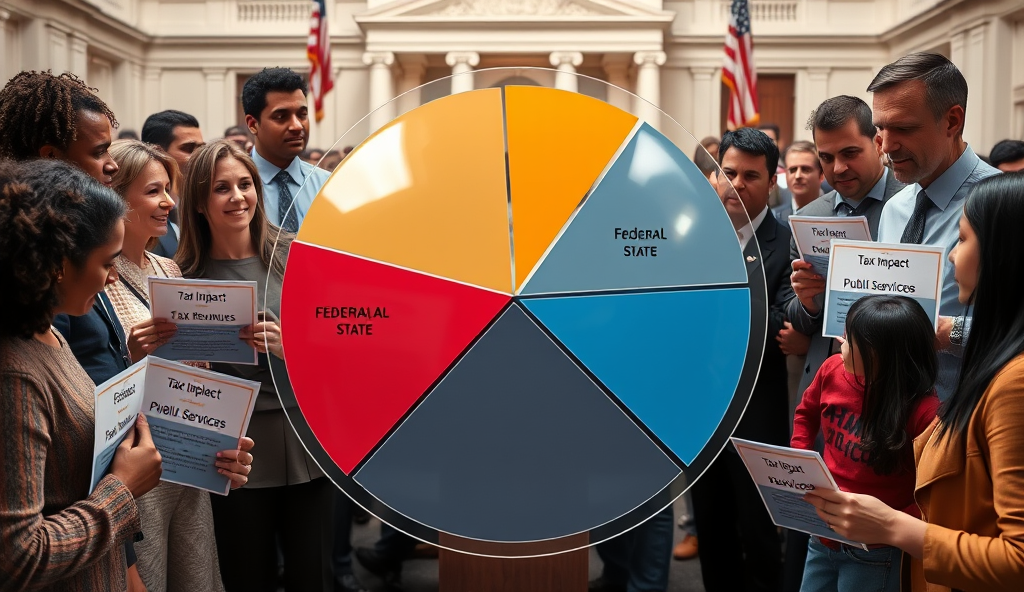

Understanding fiscal federalism in Nigeria requires examining its constitutional foundations, particularly Sections 162 and 163 of the 1999 Constitution, which outline revenue allocation principles. The current revenue allocation formula allocates 52.68% to the federal government, 26.72% to states, and 20.60% to local governments, reflecting vertical fiscal imbalance challenges.

This structure often sparks debates on resource control and fiscal autonomy, especially in oil-producing states like Rivers and Delta.

Key issues include the 13% derivation principle for mineral-rich states, which remains contentious despite being enshrined in the Constitution. For instance, states like Akwa Ibom and Bayelsa argue for higher shares due to environmental degradation from oil exploration.

Meanwhile, non-oil states advocate for equitable distribution, highlighting horizontal fiscal imbalances exacerbated by Nigeria’s diverse economic landscape.

These dynamics set the stage for deeper exploration of fiscal federalism’s core principles and their Nigerian adaptation. The next section will dissect how intergovernmental fiscal relations shape policy outcomes and citizen welfare, bridging theory with practical governance realities.

Such analysis is vital for stakeholders seeking to navigate Nigeria’s complex fiscal decentralization challenges.

Key Statistics

Introduction to Fiscal Federalism

Nigeria’s fiscal federalism operates on core principles like derivation, equity, and autonomy, which evolved from historical tensions over resource control highlighted in previous sections.

Building on Nigeria’s constitutional revenue allocation framework, fiscal federalism represents a governance model where financial responsibilities and resources are shared across federal, state, and local tiers. This system aims to balance autonomy with collective welfare, though Nigeria’s 52.68%-26.72%-20.60% vertical allocation often tilts power toward the central government, as seen in recurring disputes over oil revenue sharing.

The concept gains complexity in Nigeria’s context, where states like Rivers demand greater resource control while Kano advocates for redistribution to address regional disparities. Such tensions underscore how fiscal federalism must reconcile diverse economic realities with constitutional mandates like the 13% derivation principle.

These foundational issues pave the way for examining fiscal federalism’s precise definition and operational mechanisms in subsequent sections, particularly how intergovernmental relations influence service delivery and economic equity nationwide.

Definition of Fiscal Federalism

The federal government controls major revenue sources like oil and customs duties, while states and local governments rely on allocations from the Federation Account, creating vertical fiscal imbalances as discussed in earlier sections.

Fiscal federalism refers to the constitutional division of financial powers and revenue-sharing mechanisms between central and subnational governments, designed to balance autonomy with collective development goals. In Nigeria, this manifests through the vertical allocation formula (52.68% federal, 26.72% states, 20.60% LGAs) and horizontal principles like the 13% derivation for oil-producing states.

The system enables states to address localized needs while ensuring nationwide equity, though disputes arise when resource-rich regions like Rivers demand higher derivation percentages compared to economically disadvantaged states like Kano. Such conflicts highlight the tension between constitutional provisions and practical economic realities in Nigeria’s fiscal federalism framework.

Understanding these operational dynamics sets the stage for exploring how historical precedents shaped Nigeria’s current fiscal federalism structure, particularly the evolution of revenue allocation formulas and intergovernmental relations.

Historical Background of Fiscal Federalism in Nigeria

Nigeria’s revenue allocation formula, governed by the Federation Account, distributes resources among federal, state, and local governments, with the federal tier receiving 52.68%, states 26.72%, and local governments 20.60%.

Nigeria’s fiscal federalism traces its roots to colonial-era revenue allocation systems, notably the 1946 Richards Constitution which introduced regional autonomy and resource control debates. Post-independence, the 1963 Constitution formalized derivation-based revenue sharing, granting regions 50% of mining rents and royalties, a stark contrast to today’s 13% principle for oil-producing states.

The 1967 creation of 12 states disrupted this regional structure, centralizing fiscal powers under military rule and embedding imbalances seen in modern vertical allocation formulas. For instance, the 1970s oil boom shifted focus from agricultural taxes to petroleum revenues, intensifying conflicts over resource control between Niger Delta states and the federal government.

These historical shifts explain contemporary tensions, such as Rivers State’s demands for higher derivation percentages, while setting the stage for analyzing key principles like equity and autonomy in Nigeria’s fiscal federalism framework. The evolution underscores how past policies shape current intergovernmental fiscal relations and revenue allocation disputes.

Key Principles of Fiscal Federalism

Nigeria’s flawed fiscal federalism directly constrains GDP growth, with states contributing just 12% to national revenue despite controlling 60% of population-driven economic activities like agriculture and SMEs.

Nigeria’s fiscal federalism operates on core principles like derivation, equity, and autonomy, which evolved from historical tensions over resource control highlighted in previous sections. The derivation principle, currently pegged at 13% for oil-producing states, contrasts sharply with the 50% regional entitlement under the 1963 Constitution, reflecting ongoing debates about fair revenue allocation in intergovernmental fiscal relations.

Equity ensures balanced development across states through horizontal allocation formulas, though disparities persist as seen in the Niger Delta’s demands for higher shares of petroleum revenues. Fiscal autonomy, weakened by military-era centralization, remains contentious as states like Lagos push for greater control over VAT collection, challenging the federal government’s dominance in taxation and fiscal decentralization.

These principles shape Nigeria’s revenue allocation formula, setting the stage for analyzing the structural layers of fiscal federalism in the next section. The interplay between resource control and constitutional provisions continues to define intergovernmental fiscal relations, with oil revenue sharing at the heart of vertical imbalances.

Structure of Fiscal Federalism in Nigeria

Nigeria’s fiscal federalism framework remains contentious, with persistent debates over revenue allocation formula in Nigeria and the derivation principle’s implementation.

Nigeria’s fiscal federalism operates through a three-tiered structure comprising the federal, state, and local governments, each with constitutionally defined revenue powers and expenditure responsibilities. The federal government controls major revenue sources like oil and customs duties, while states and local governments rely on allocations from the Federation Account, creating vertical fiscal imbalances as discussed in earlier sections.

This structure is further complicated by overlapping functions, such as concurrent responsibilities in education and healthcare, which often lead to intergovernmental fiscal relations disputes. For instance, states like Rivers and Lagos have challenged federal dominance in tax collection, reflecting tensions over fiscal decentralization highlighted previously.

The next section will examine how these structural dynamics influence Nigeria’s revenue allocation formula, particularly the contentious sharing of oil revenues and VAT proceeds. These debates underscore the ongoing struggle to balance autonomy with equitable distribution in Nigeria’s fiscal federalism framework.

Revenue Allocation in Nigeria

Nigeria’s revenue allocation formula, governed by the Federation Account, distributes resources among federal, state, and local governments, with the federal tier receiving 52.68%, states 26.72%, and local governments 20.60%. This vertical sharing often sparks debates, particularly from oil-producing states advocating for higher derivation-based allocations beyond the current 13% for mineral-rich regions.

The horizontal allocation among states uses factors like population (30%), equality (40%), and landmass (10%), yet critics argue this undermines fiscal autonomy, as seen in Lagos State’s push to retain VAT revenues. Such disputes reflect deeper tensions in Nigeria’s fiscal federalism, where resource control clashes with equitable redistribution goals.

These dynamics set the stage for examining the distinct roles of federal, state, and local governments in Nigeria’s fiscal framework, particularly how their constitutionally assigned functions intersect with revenue realities.

Roles of Federal State and Local Governments

The federal government controls nationwide functions like defense, foreign policy, and monetary regulation, funded by its 52.68% revenue share, while states manage education, health, and intra-state infrastructure with their 26.72% allocation. Local governments, receiving 20.60%, handle primary services like sanitation and rural roads, though their effectiveness is often hampered by limited autonomy and delayed federal transfers.

Constitutionally, states like Lagos argue for greater fiscal autonomy to address unique urban challenges, exemplified by their VAT collection dispute with the federal government. Meanwhile, oil-producing states demand higher derivation-based allocations, claiming the current 13% undermines their capacity to mitigate environmental degradation and fund development projects.

These role delineations create friction when revenue realities diverge from constitutional mandates, setting the stage for examining systemic challenges in Nigeria’s fiscal federalism. The next section explores how these tensions manifest in operational inefficiencies and intergovernmental conflicts.

Challenges of Fiscal Federalism in Nigeria

Nigeria’s fiscal federalism faces systemic hurdles, including delayed federal transfers that cripple state and local governments’ ability to deliver services, as seen in 2022 when 23 states struggled to pay salaries due to withheld allocations. The rigid revenue allocation formula exacerbates disparities, with non-oil states like Kano receiving just 4.3% of federal revenue despite contributing significantly to agriculture and commerce.

Intergovernmental conflicts arise from overlapping mandates, such as the federal government’s encroachment on state responsibilities like primary healthcare, creating inefficiencies. Oil-producing states like Rivers and Bayelsa highlight the inadequacy of the 13% derivation principle, which fails to offset environmental costs or fund alternative development projects beyond oil dependence.

These structural imbalances perpetuate dependency on oil revenues, stifling subnational innovation and deepening fiscal inequalities. The next section examines how these challenges directly hinder Nigeria’s broader economic development goals.

Impact of Fiscal Federalism on Economic Development

Nigeria’s flawed fiscal federalism directly constrains GDP growth, with states contributing just 12% to national revenue despite controlling 60% of population-driven economic activities like agriculture and SMEs. The overcentralized revenue allocation formula discourages productivity, as seen when Lagos generates 65% of VAT receipts but receives only 20% of redistributed funds, stifling its potential as an economic hub.

Persistent intergovernmental conflicts over resource control create policy instability, deterring foreign investment in sectors like solid minerals where states like Nasarawa could thrive. Oil-dependent states like Delta record 70% unemployment rates despite receiving derivation funds, proving current fiscal structures fail to translate revenues into diversified development.

These systemic inefficiencies perpetuate Nigeria’s ranking as 131st in World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index, with subnational governments unable to fund critical infrastructure. The next section compares these outcomes with functional fiscal federalism models in Brazil and India, highlighting actionable reforms.

Comparative Analysis with Other Countries

Unlike Nigeria’s centralized model, Brazil’s fiscal federalism allows states to retain 25% of VAT collections, incentivizing regional productivity as seen in São Paulo’s 33% GDP contribution. India’s Finance Commission ensures 42% of central taxes go directly to states, enabling Karnataka to invest 18% of its budget in tech infrastructure, contrasting with Lagos’ infrastructure deficit despite generating 65% of Nigeria’s VAT.

While Nigeria struggles with oil dependency, Indonesia’s 2001 decentralization law shifted 40% of natural resource revenues to producing regions, reducing poverty in Aceh by 50% within a decade. South Africa’s equitable share formula allocates funds based on population (45%), poverty (30%), and economic output (25%), unlike Nigeria’s arbitrary revenue allocation formula that ignores productivity metrics.

These models demonstrate how constitutional provisions on fiscal federalism can address vertical imbalances, offering Nigeria templates for reform. The next section examines recent policies attempting to correct these disparities, including the 2022 Fiscal Federalism Bill and revised derivation principles.

Recent Reforms and Policies

Nigeria’s 2022 Fiscal Federalism Bill proposed constitutional amendments to increase states’ VAT retention to 35%, mirroring Brazil’s model, while the revised derivation principle raised oil-producing states’ share from 13% to 21%, partially addressing resource control demands like Indonesia’s Aceh precedent. However, implementation gaps persist as Lagos still receives only 20% of its generated VAT despite contributing 65% nationally.

The Finance Act 2023 introduced population (30%) and poverty (25%) metrics into revenue allocation, borrowing from South Africa’s equitable share formula, though economic output indicators remain excluded unlike India’s 42% devolution framework. These reforms face resistance from federal agencies controlling 52.68% of distributable pool, highlighting structural challenges in vertical fiscal imbalance resolution.

Emerging state-level initiatives like Edo’s 18% IGR growth through property tax reforms demonstrate localized fiscal autonomy potential, setting the stage for examining future systemic changes. The next section explores how these policy shifts could reshape Nigeria’s fiscal federalism landscape amid calls for constitutional restructuring.

Future Prospects of Fiscal Federalism in Nigeria

Nigeria’s fiscal federalism trajectory hinges on resolving the tension between centralized revenue control and state-level autonomy, as seen in Lagos’ VAT contribution disparity and Edo’s successful property tax reforms. The 2023 Finance Act’s inclusion of poverty metrics may gradually rebalance allocations, though full adoption of economic productivity indicators—as practiced in India—remains critical for equitable resource distribution.

Constitutional restructuring could address vertical fiscal imbalances by redefining the 52.68% federal share of distributable revenue, potentially adopting Brazil’s state VAT retention model more comprehensively. Emerging debates mirror Indonesia’s Aceh precedent, with oil-producing states advocating for further derivation principle adjustments beyond the current 21% cap to reflect resource control realities.

State-driven innovations like Kano’s land use charge reforms and Rivers’ IGR diversification suggest a shift toward competitive federalism, provided federal agencies cede fiscal authority. These developments set the stage for systemic evaluation in the concluding section, where Nigeria’s fiscal federalism model will be assessed against global benchmarks for sustainability and equity.

Conclusion on Fiscal Federalism in Nigeria

Nigeria’s fiscal federalism framework remains contentious, with persistent debates over revenue allocation formula in Nigeria and the derivation principle’s implementation. The 13% oil revenue sharing in Nigerian federalism, though a step forward, still sparks tensions between oil-producing states and the federal government.

Challenges like vertical and horizontal fiscal imbalance in Nigeria hinder equitable development, as seen in disparities between Lagos’ internally generated revenue and states reliant on federal allocations. Constitutional provisions on fiscal federalism in Nigeria need revisiting to address these gaps and strengthen state and local government fiscal autonomy.

Moving forward, effective fiscal decentralization in Nigeria requires balancing resource control with national cohesion while tackling taxation and fiscal federalism inefficiencies. These reforms must prioritize transparency and accountability to ensure sustainable intergovernmental fiscal relations in Nigeria.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does the 13% derivation principle affect oil-producing states like Rivers and Delta?

The 13% derivation provides additional revenue to oil-producing states but often falls short of addressing environmental costs; states can leverage the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC) for supplementary funding.

What practical steps can non-oil states take to improve revenue generation under Nigeria's fiscal federalism?

Non-oil states like Kano can boost internally generated revenue (IGR) by digitizing tax collection and expanding agricultural value chains as seen in Kebbi's rice revolution.

How can citizens track how fiscal federalism allocations are spent in their states?

Use tools like BudgIT's Tracka platform to monitor state budget implementation and demand accountability from local representatives.

What impact does the 52.68% federal revenue share have on service delivery at state level?

The high federal share often starves states of funds for critical services; advocate for constitutional reforms to rebalance allocations through state assemblies.

Can states legally challenge the current VAT collection system like Lagos did?

Yes states can pursue legal action citing constitutional provisions on fiscal federalism but should first build strong IGR systems as backup like Lagos' property tax model.