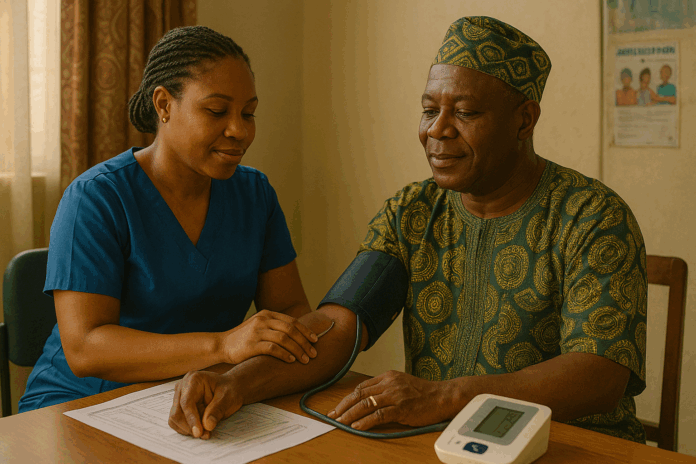

Imagine a health crisis quietly unfolding across homes, marketplaces, and clinics in Nigeria—an invisible epidemic of high blood pressure, striking silently and striking hard. Today, the Federal Government has sounded the alarm: many hypertension cases in the country remain undiagnosed, a revelation that underscores a deepening public health concern.

Across Nigeria, hypertension—also known as high blood pressure—has surged to alarming levels. A rigorous nationwide survey in 2017 revealed that 38.1% of Nigerian adults meet clinical criteria for hypertension, with rates rising above 50% in some regions. Despite these staggering numbers, awareness remains stubbornly low. Studies focusing on North Central Nigeria documented that while 23.3% of men had hypertension, only 7.1% knew their diagnosis. More broadly, national analyses show that over half of hypertensive Nigerians are untreated or poorly controlled.

The Federal Government’s recent warning is both urgent and overdue. Undiagnosed and unmanaged hypertension is often referred to as the “silent killer” because symptoms may not emerge until irreversible damage occurs. Strokes, kidney failure, heart attacks, and sudden cardiac death can all follow unchecked blood pressure elevation.

As a lifestyle blogger committed to factual reporting, my mission is to explore this issue with clarity and depth: Why are so many Nigerians unaware of their hypertension? What personal and structural barriers exist? And how can individuals and communities act before tragedy strikes?

In the following sections, we’ll unpack the scope of the problem, root causes, governmental strategies, expert insights, and concrete actions you can take—every claim anchored in trusted data and the latest public health developments.

Scope of the Issue in Nigeria

Prevalence & Awareness

Hypertension has become a national ticking time bomb. A 2017 nationwide survey across Nigeria found an age-standardized prevalence of 38.1%, with regional highs reaching 52.8%. Recent analyses confirm prevalence ranging from 22% to 44%. Nearly 19 million Nigerian adults aged 30–79 live with hypertension.

Yet less than a third of those affected actually know it. Studies estimate only 29% are aware, with awareness dropping as low as 7–17% in rural communities. Treatment rates hover around 12%, and only 3–12% achieve blood pressure control below 140/90 mmHg.

Undiagnosed and Uncontrolled Cases

The term “undiagnosed hypertension” is chillingly apt. In various Nigerian communities, between 20% and over 60% of hypertensive individuals are completely unaware of their condition. One university-based study found that 27.8% of staff were hypertensive without knowing it. A national review spanning 1995 to 2020 showed only 29% awareness, 12% on treatment, and a mere 2.8% achieving control.

This means millions of Nigerians unknowingly walk toward major health crises—sudden strokes, heart attacks, chronic kidney disease, and cardiac arrest. Experts have long warned this is the “silent killer” at work.

Health Consequences

When hypertension is untreated or uncontrolled, its consequences unfold mercilessly. Data show hypertension contributes significantly to Nigeria’s cardiovascular disease burden, accounting for about 11% of all deaths. Around 25% of emergency admissions in urban hospitals are tied to hypertension-related complications such as strokes, heart failure, and hypertensive crises.

The impact is profound and personal. Families face lost productivity, financial hardship, and emotional trauma. Public health systems buckle under preventable complications. Undiagnosed hypertension isn’t just an individual issue—it’s a national emergency.

Underlying Causes & Risk Factors

Systemic Barriers

Limited Screening & Access: Only a fraction of Nigerians ever get their blood pressure measured. Public health campaigns like World Hypertension Day help, but regular screening at primary health centers remains rare. Rural communities suffer most—many PHCs lack equipment, power, or trained staff.

Healthcare Financing & Costs: Nigeria spends around 5% of its GDP on health, with the federal government contributing just 1.5%. Most citizens pay out of pocket. Currency devaluation inflates medication prices, making treatment unaffordable—especially in rural areas.

Primary Healthcare Weaknesses: Despite reforms, many PHCs lack staff, medications, or equipment. Programs like WHO’s HEARTS and the National Hypertension Control Initiative exist but are confined to pilot regions.

Low Insurance Coverage: The National Health Insurance Scheme covers only a small fraction of the population. Rural and informal-sector workers largely remain uninsured.

Individual Lifestyle & Behaviors

Sedentary Lifestyle & Poor Diet: Urbanization has driven higher consumption of processed, salty foods, and daily physical activity has dropped significantly in cities.

Alcohol & Tobacco Use: Though still lower than in Western nations, consumption is rising—especially among youth—contributing to hypertension risk.

Low Health Literacy & Cultural Beliefs: Many Nigerians believe hypertension must show symptoms. When it doesn’t, individuals remain undiagnosed. Self-medication and use of herbal remedies delay proper diagnosis and treatment.

Treatment Adherence Gaps: It’s common for patients to stop medication once they feel better. This leads to uncontrolled blood pressure and increases the risk of stroke, heart attack, and kidney disease.

Federal Government Policy Response

Screening & Early Detection

Project 10 Million: A campaign to screen 10 million Nigerians for hypertension and diabetes under the slogan “Know Your Number, Control Your Number.”

Free Medical Outreach in FCT: Blood pressure screenings were held in clinics, mosques, and churches throughout Abuja to encourage regular monitoring.

National Targets: The Ministry of Health aims to screen 80% of eligible adults, treat 80% of those diagnosed, and achieve blood pressure control in 80% of treated individuals—aiming to reduce premature cardiovascular deaths by 25%.

Medication and Pharmaceutical Strategy

Drug Revolving Fund: Established at PHCs to ensure consistent, affordable access to hypertension medications.

Duty Waivers & Local Production: The government has waived import duties on antihypertensive drugs and encouraged domestic manufacturing to reduce cost and dependence on imports.

Systems‑Level Reforms

National Hypertension Control Initiative (NHCI): Launched in 2020 in partnership with WHO and state governments. It uses WHO’s HEARTS package—standard protocols, task sharing, health information systems, counseling, and drug funds.

Hypertension Treatment in Nigeria (HTN) Program: Operating in 60 PHCs across FCT, Ogun, and Kano. As of December 2023, treatment coverage exceeded 90%, and control rates reached 50% for about 21,000 patients.

Policy Guidance & Standards: In 2024, the government released six NCD policy documents, including national hypertension guidelines, task-shifting frameworks, and tobacco and fat regulations.

Health Sector Renewal Compact: Signed in 2023, this agreement commits the government and donors to strengthen PHC systems under the National Health Act and the Basic Health Care Fund.

Expert Perspectives & Civil Society Input

Experts and associations have delivered stark, urgent assessments.

May & Baker’s Managing Director warned that undiagnosed hypertension is fueling sudden deaths and heart attacks. He stressed affordable medication and regular blood pressure monitoring as critical.

Medical authorities have described growing “slump and die” cases linked to unmanaged hypertension. They promote prevention: physical activity, diet changes, and salt reduction.

Nigerian Cardiac Society reported that over 30% of adults are hypertensive and unaware.

Nigerian Hypertension Society confirmed one in three adults has hypertension. Most are undiagnosed or untreated, and few who are treated achieve normal blood pressure.

National studies show alarmingly low awareness (29%), treatment (12%), and control (2.8–10%) rates.

The consensus is clear: Nigeria faces a silent hypertension epidemic that demands immediate action—from community screening and affordable treatment to education and lifestyle change.

Recommendations & Solutions

Increase Public Awareness

Launch salt‑reduction campaigns targeting a 30% drop in sodium intake to under 2 g per day. Use mass media and grassroots outreach with slogans like “turn down the salt” and “know your number.” Involve industry, regulatory bodies, and civil society.

Scale Screening and PHC Capacity

Expand the HTN Program nationally. Equip every PHC with calibrated blood pressure machines, trained staff, and standardized protocols. Sustain drug revolving funds and integrate chronic care funding into the Basic Health Care Fund.

Improve Access to Affordable Medicines

Maintain drug revolving funds at PHCs, support local pharmaceutical production, and include hypertension treatment in health insurance schemes.

Promote Long‑term Lifestyle Change

Encourage low‑sodium cooking habits. Promote physical activity through urban design and community programs. Reinforce alcohol and tobacco regulations. Provide health coaching and home blood pressure monitoring to improve adherence and control.

Strengthen Monitoring & Research

Integrate hypertension indicators into the national health information system. Conduct periodic national NCD surveys—Nigeria hasn’t done one since the 1990s—to track progress. Fund research on program implementation and sodium reduction policy outcomes.

Conclusion

Nigerians face a pivotal moment. One in three adults has hypertension, yet awareness (29%), treatment (12–20%), and control (3–10%) remain unacceptably low. This silent epidemic drives strokes, heart disease, kidney failure, and premature death.

The Federal Government’s comprehensive response—including screenings, the NHCI, the HTN Program, new policy guidelines, and sodium reduction targets—marks a decisive start. Pilot results—90% treatment rate and 50% control—demonstrate what’s possible.

But success hinges on scale:

- Political and financial commitment to nationwide expansion

- Equipped PHCs, trained staff, and sustained medication funding

- Public engagement that moves from awareness to action

- Routine monitoring, national surveys, and transparent data sharing

Every Nigerian can play a role:

- Know your numbers. Get screened annually.

- If diagnosed, stay on treatment—even when you feel well.

- Advocate for quality primary care in your community.

- Embrace healthy habits: reduce salt, eat well, stay active.

With well-funded systems, informed communities, and personal responsibility, Nigeria can rewrite its hypertension story. This isn’t just public health—it’s a shared responsibility for the well-being of every citizen.