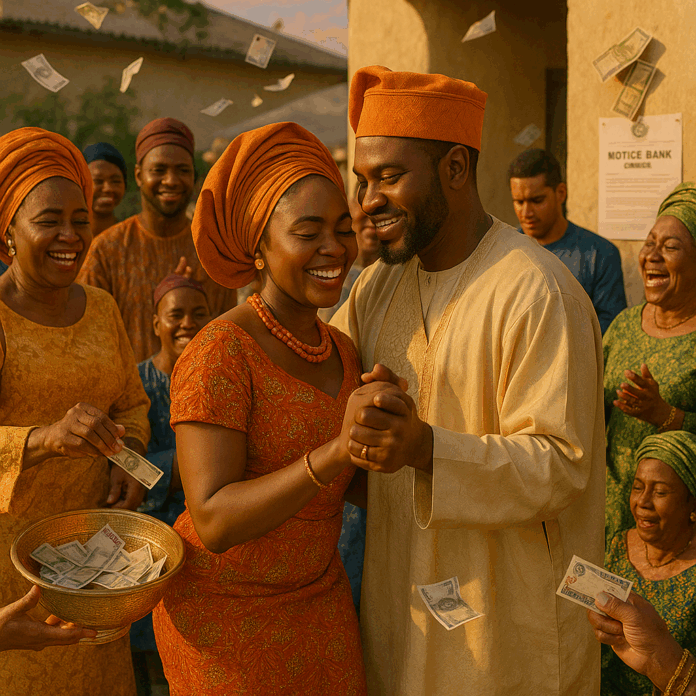

You know how Nigerian weddings and celebrations—especially within Yoruba communities—are filled with vibrant colors, music, and one of the most iconic moments: the ritual of “spraying” money? Guests enthusiastically shower the bride, groom, or performers with crisp naira notes—a joyous act symbolizing generosity, celebration, and social support. But lately, those scenes are changing, and not for festive reasons.

There’s been an unmistakable sense of tension in the air. Over the past months, the government has dramatically stepped up enforcement of an eight‑year‑old law that bans spraying, dancing on, or defacing naira notes. The penalties aren’t trivial—up to six months in prison or a ₦50,000 fine. The EFCC (Economic and Financial Crimes Commission) and the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) aren’t holding back anymore: influencers, entertainers—even well‑known socialites—are being arrested and publicly prosecuted.

Why now? The answer ties directly to the phrase driving this story: cultural shift amid economic strain. The naira has lost roughly 70% of its value over the past two years, inflation is soaring, and the CBN is desperately trying to restore trust in the currency. In that context, spraying is painted not just as cultural exuberance, but as reckless disrespect of the national symbol.

This crackdown isn’t just about money—it’s a collision between rich cultural heritage and hard financial reality. The tradition that once marked love, honor, and communal support is now being reframed as something dangerously frivolous. For many Nigerians, what used to feel like celebration now feels like potential legal trouble. And that shift—emotional, cultural, economic—is exactly what this story explores.

Origins & Cultural Significance of Spraying

Historical Roots

Spraying traces back to southwestern Nigeria, especially among the Yoruba. It began subtly in the early 20th century, with families discreetly placing folded naira or coins in pockets as a token of support. During the oil boom of the 1960s and 1970s, this modest gesture evolved into public spectacle: guests tossing crisp naira notes at celebrants became a way to showcase prosperity and social status. Rooted in the Yoruba practice of owambe parties and tied to juju music and praise singing, spraying became not only a sign of wealth but of communal appreciation.

Symbolism & Social Function

Spraying became much more than money. It represents blessings, generosity, and community solidarity. It’s both intimate and performative—guests offering love and respect while enjoying the festive moment. Over time, the practice spread to various ethnic groups—Igbo, Hausa, Edo, Delta, and even into diaspora communities. A secondary economy emerged: vendors selling fresh bills, assistants collecting and redistributing money, and entertainers incorporating spraying into their earnings. It’s a deeply interwoven cultural gesture.

Economic Pressure & Value of the Naira

Drastic Currency Depreciation

Since mid‑2023, after the CBN floated the naira, it lost nearly 70% of its value—from roughly ₦600 to over ₦1,500 against the dollar by early 2025. Informal market rates and official rates reflected the steep decline, reflecting deep macroeconomic pressure.

Inflation Surge

Annual inflation skyrocketed, hitting nearly 35% at its worst and lingering into the mid‑20s percent range in 2025. Food inflation was particularly brutal: rice, grains, and even sachet water saw sharp price increases.

Monetary Tightening

In response, the CBN raised its Monetary Policy Rate from under 20% to over 27%. Major reforms accompanied the float—including subsidy removal and forex policy changes—to stabilize inflation and currency value.

Oil Dependence and Fiscal Strain

Nigeria’s revenue remains tied to oil. Price drops undermine the naira and fuel inflation. To mitigate economic instability, the government requested over $21 billion in foreign loans in mid 2025.

Currency Abuse as Symbolic Symptom

Against this backdrop, spraying is seen as disrespectful. Damaged notes cost the central bank money to reprint and replace. Authorities frame spraying as a symbol of recklessness—a misuse of currency that undermines public effort toward economic recovery. Critics say this symbolic focus distracts from deeper fiscal issues like forex shortages and governance weaknesses. Meanwhile, for ordinary Nigerians, spending discretionary income on spraying during hardship feels increasingly punishing.

Legal & Regulatory Framework

Section 21 of the CBN Act (2007)

This section criminalizes tampering with or defacing naira notes. Offenders face at least six months in prison, or a ₦50,000 fine, or both. Subsection (3) explicitly bans spraying, dancing on, or littering naira notes on the floor—and subsection (4) bans hawking or trading them outside formal channels.

Who Enforces It

The CBN, EFCC, Nigeria Police, and Nigeria Financial Intelligence Unit collaborate. The EFCC leads arrests and prosecutions under its mandate to tackle financial crimes.

High‑Profile Enforcement Cases

A makeup artist known as Amuscap was jailed for six months in April 2025 after spraying ₦100,000 at his own wedding. Two Lagos content creators were convicted in May 2025 and given six months or ₦200,000 fine for spraying. Influencers like Bobrisky received six‑month sentences in April 2024, without option of fine. Socialites like Cubana Chief Priest and Nollywood actress Oluwadarasimi Omoseyin received similar legal treatment in 2024.

Legal Debates

Some defenders argue that cultural gestures should not be treated like intentional currency destruction. Legal nuance is sought—one that differentiates harmless tradition from economic harm. Critics say the law lacks sensitivity and is being used without flexibility.

Government Rationale vs Criticism

Government’s Justifications

Protecting the integrity of physical currency and reducing replacement costs.

Promoting monetary discipline to complement subsidy cuts, naira float, and reform.

Rebuilding public trust in the naira by establishing respect for the note as a national symbol.

Criticisms & Counterpoints

Economic impact is minimal—spraying doesn’t materially affect inflation or forex reserves.

The law suppresses cultural expression and fails to distinguish between celebration and intentional destruction.

Enforcement is seen as uneven—ordinary Nigerians are prosecuted, while elites often escape scrutiny.

Critics view it as symbolic government messaging, distracting from tackling corruption, improper forex management, and policy failures.

Visible displays of wealth during hardship are increasingly controversial and tone‑deaf, raising social equity concerns.

Cultural Shift & Adaptations

Behavioral Changes

Celebrations now feature discreet money bowls, envelope gifting, or off‑camera sprays. Guests avoid fresh bills and keep money off dance floors to evade detection.

Creative Alternatives

Prop or imitation money that looks festive but isn’t legal tender.

Decor envelopes, voucher systems, or tokens that capture the celebratory act without violating the law.

Digital tipping via mobile apps like Opay or Flutterwave during performances.

Some upscale events feature spraying of foreign currency—dollars or pounds—to evade naira laws.

Broader Implications: Culture, Economy & Identity

Cultural Erosion vs Innovation

Blanket enforcement threatens shared customs. Cultural scholars suggest regulated exemptions instead of outright bans. Adaptation through imitation currency shows resilience and respect for tradition.

Economic Symbolism and Inequality

Spraying has shifted from heartfelt blessing to wealth display. Amid staggering inequality—where five people hold billions while over 112 million live in poverty—those who spray may seem flaunting privilege. Inflation and hardship sharpen this contrast.

State Influence on National Norms

The crackdown is part of a broader campaign to foster patriotic respect for the naira. Yet selective prosecutions—especially when elites go unpunished—undermine legitimacy. The tension is between symbolic nation‑building and perceived performative enforcement.

Final Thoughts

We’ve traced how a vibrant cultural tradition is colliding with harsh economic realities in Nigeria. Criminalizing spraying under economic strain marks a historic cultural pivot.

Preservation vs Punishment: A long‑standing practice is now penalized under Section 21 of the CBN Act. Without nuance, Nigeria risks eroding proud traditions.

Symbolic Politics with Limited Effect: Spraying is visible but not economically significant. Critics debate whether real reforms—fiscal discipline, governance, anti‑corruption—should take priority.

Cultural Reinvention: Communities are innovating—using fake notes, envelopes, digital transfers—to preserve ceremony without legal risk.

Cultural Citizenship and National Values: The state is attempting to shape a new cultural respect for currency. But for many, the crackdown feels like misprioritized enforcement.

Celebration must endure, especially during hardship—but it needs pathways that honor both tradition and law. Policymakers should distinguish between literal currency abuse and symbolic cultural expression. Hybrid solutions—regulated spraying spaces, public education, digital alternatives—offer hope.

This is more than a viral social media moment. It’s a test of Nigeria’s ability to adapt and sustain its heritage under pressure. Can a nation honor its past while navigating economic survival? The answer will define both its currency and its character.